Carbon transport & storage

Introduction to the infrastructure needed to develop a functional carbon transport and storage networks for port officials and industrial emitters implementing CCS.

Building carbon transport and storage infrastructure is a gigantic logistics challenge involving many different people. From plant managers deploying carbon capture systems to port officials developing CO₂ import/export terminals, everyone brings specialised knowledge yet differing assumptions, so a shared understanding of the components needed to create an economical value chain is critical. That means getting familiar with how carbon capture technologies work, zero carbon shipping, the role of land development in building infrastructure, and why ports are vital for CO₂ economies.

Terminology

Carbon transport and storage (CTS) is the infrastructural and logistical link in the carbon capture and storage (CCS) value chain (Energistyrelsen2024, p. 96), which is a subcategory of the carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS) industry. It focuses on transporting captured carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions, usually in a liquefied state, from emissions point sources to secure storage sites or utilisation hubs, while preventing their release into the atmosphere. This infrastructure is essential for industrial decarbonisation, especially in hard-to-abate sectors like cement, steel, and chemicals, where directly reducing emissions remains challenging if not impossible.

- Carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) encompasses the full carbon value chain, from CO₂ capture at point sources to direct air capture, utilisation to produce other resources, including transport, and permanent sequestration in geological formations.

- Carbon capture and storage (CCS) encompasses CO₂ capture from an industrial or utility plant, followed by transport, and permanent sequestration.

- Carbon capture and utilisation (CCU) encompasses utilising captured CO₂ as a resource, for instance in producing e-fuels, adding a circular economy dimension.

- Carbon transport and storage (CTS) encompasses the infrastructure (ships, pipelines, railways, import/export terminals, tanks) and logistics needed to collect, process, transport, distribute, and store captured CO₂ at an intermediate or final destination.

Demand

In 2022, human activity released over 40 billion tons of CO₂ from fossil fuels—enough to cover Alaska, Texas, and California under eight meters of gas. CTS provides the backbone for managing this unimaginable volume, enabling large-scale decarbonisation. Despite a chicken-and-egg dilemma—emitters awaiting infrastructure, developers awaiting supply—progress is clear. The EU directive on geological storage emerged in 2009, Bellona has advocated CCS since 1986, and billions in private capital, like BlackRock’s U.S. investments and the Northern Lights project (co-funded with Norway), signal growing demand and viability.

Carbon transport

Transporting CO₂ requires methods tailored to volume, distance, cost, safety, and environmental impact.

- Pipelines: The most cost-effective for large-scale, long-distance transport, especially onshore. CO₂ is compressed to a supercritical state (above 73.8 bar, 31°C), flowing efficiently over hundreds of kilometers. Repurposed oil and gas pipelines can reduce costs, though new builds face specification, permitting and corrosion challenges (CO₂ reacts with steel in moist conditions).

- Ships: Ideal for offshore or cross-border routes, CO₂ is liquefied at -50°C and 7-15 bar for transport in specialised vessels. Ships excel where pipelines are impractical, but they require dedicated port infrastructure for loading/unloading etc.

- Trucks and trains: Suited for smaller volumes or shorter distances, these methods haul CO₂ in pressurised cylinders (20-50 bar) to intermediate hubs. Flexible but low-capacity (20-40 tonnes per truck), they bridge to pipelines or ships.

Carbon storage

CTS employs temporary and permanent storage, each with unique demands. Permanent sites need extensive geological surveys and monitoring, mandated by permits. Offshore storage dominates in Europe, but onshore exploration grew in 2023 in Denmark and beyond.

Intermediate storage

Temporary facilities store liquefied CO₂ in tanks at ports or hubs, smoothing logistics between capture and final transport. These buffers are vital for ship scheduling or pipeline batching, with capacities depending on throughput.

Permanent storage

CO₂ is injected into geological formations at kilometer depths, where it remains trapped by pressure and cap rocks.

- Depleted oil and gas reservoirs: Proven to trap fluids for millennia, these sites have been used since the 1970s in the U.S. for enhanced oil recovery (EOR), marking an early form of CO₂ storage.

- Deep saline aquifers: Often located 1-3 km underground, these formations hold saline water unfit for use, offering gigatonnes of pore space and impermeable cap rocks. Injection requires precise pressure management to avoid fracturing.

- Unmineable coal seams: CO₂ adsorbs onto coal at 50-100 bar, displacing methane for energy recovery. Capacity varies (5-20 kg CO₂/tonne) with depth and permeability.

Industrial clusters

Industrial clusters aggregate CO₂ from emitters like refineries, steelworks, and cement plants into central hubs, often at harbours, for economies of scale. This cuts per-tonne costs (e.g., $50-100/tonne savings), making CTS viable and bankable. The Porthos project in Rotterdam pipes 2.5 Mt/year to offshore storage, while the UK’s Net Zero Teesside hub targets 4 Mt/year by 2030 with North Sea sequestration.

Hubs share pipelines, liquefaction plants, and terminals, easing capital burdens for smaller emitters. Harbour hubs like Northern Lights handle 5 Mt/year, storing CO₂ temporarily before offshore shipping. This ensures steady supply and revenue, drawing private investment. Cross-border networks like TEN-T boost scalability.

Incentives

The growth of carbon transport and storage (CTS) infrastructure relies on tailored regulatory and economic frameworks that address regional needs. In the European Economic Area (EEA), tools like the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) guide investment by pricing emissions, levelling the playing field for cross-border trade, and nudging companies toward low-carbon production.

Europe

At the heart of carbon regulation in the EEA lies the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), a market-driven tool that shapes CTS infrastructure investment.

EU emmissions trading system

Since its launch in 2005, the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) has grown into the world’s first major carbon market, tackling emissions of CO₂, nitrous oxide (N₂O), and per-fluorocarbons (PFCs) from sectors like power generation, manufacturing, and aluminum production (added in 2020). Spanning the EU, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein, this cap-and-trade system sets an annual emissions ceiling for covered industries. That cap is divvied up into EU Allowances (EUAs)—each representing one tonne of CO₂—which companies trade on platforms like the European Energy Exchange (EEX).

Every year, businesses must report their emissions, facing steep fines—starting at €100 per tonne, adjusted for inflation—for any shortfall, though some exemptions exist. Revenue from EUA sales flows into initiatives like the Modernisation Fund, fuelling carbon-neutral tech development. Since 2021, the emissions cap has tightened by 2.2% annually, pushing toward a climate-neutral market by the mid-2030s. Still, the ETS’s future sparks debate, with price swings and speculation by private traders stirring concerns.

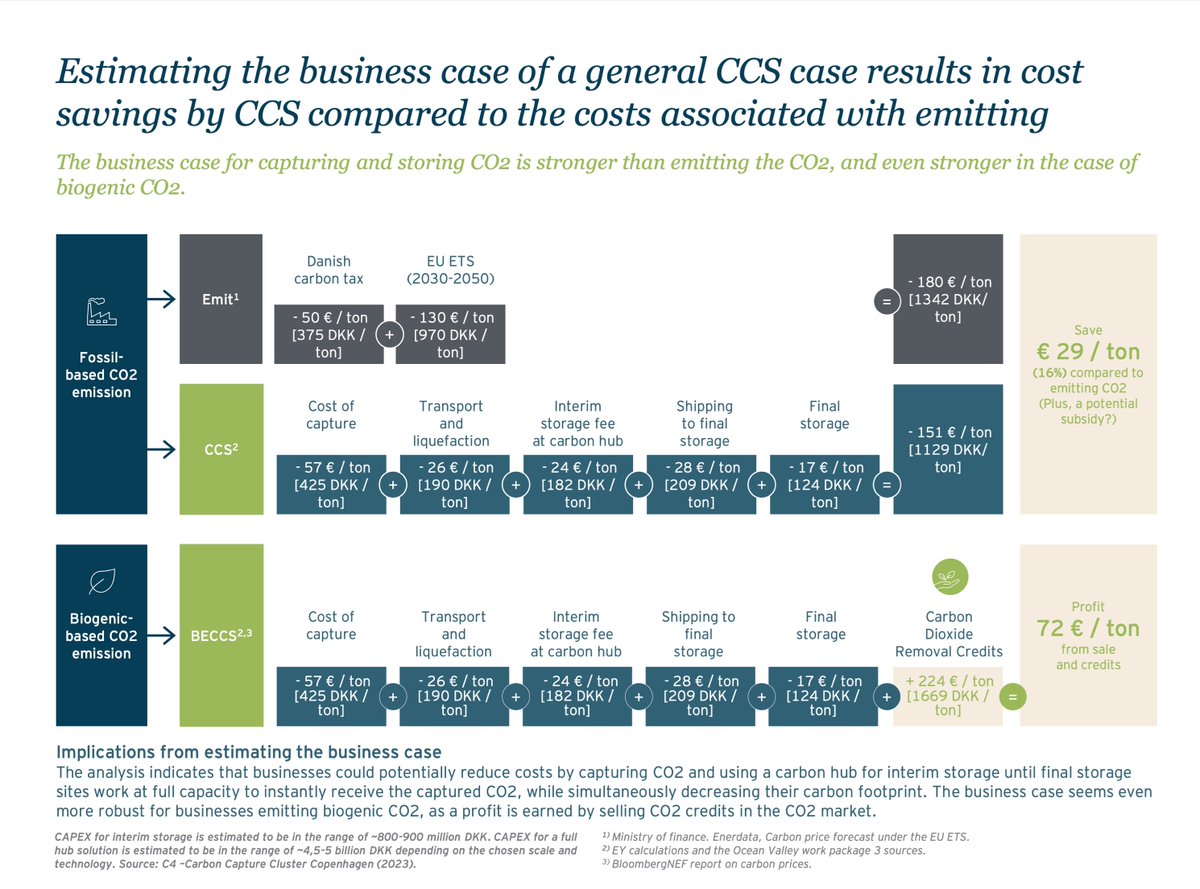

EUA prices directly sway CTS adoption. When prices dip below the cost of carbon capture and storage (CCS), companies might just buy allowances instead of building infrastructure. But when prices climb, emissions become a costlier burden, spurring investment in transport and storage solutions to dodge penalties and boosting demand for CTS systems, as noted by the European Commission.

Businesses can trade EUAs on exchanges like EEX or the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE). For individuals, options include financial products like the KRBN ETF (two-thirds EUAs), the iPath Series B Carbon ETN (99% EUAs), or CU3RPS trackers.

Carbon border adjustment mechanism

Complementing the EU ETS, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) slaps fees on carbon-heavy imports, aligning their costs with goods produced under the ETS. By tackling carbon leakage, it requires importers to register, purchase CBAM certificates, and report emissions. This not only bolsters CTS investment but also nudges global supply chains toward lower emissions, per the European Commission.

United States of America

Across the Atlantic, the U.S. takes a different tack, leaning on direct funding and legislation rather than a cap-and-trade model to propel CTS, with the Department of Energy (DOE) leading the charge.

- Bipartisan Infrastructure Law: The 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act pumps $8.2 billion into CCS, including transport networks like pipelines and ships, as detailed by the Congressional Budget Office and Energy News.

- DOE Funding Programs: Through the CIFIA program, the DOE dishes out $500 million for CO₂ transport projects. Meanwhile, $45.6 million backs nine efforts to refine capture and storage tech, according to the National Energy Technology Laboratory.

- Future Growth Grants: The CIFIA initiative also seeds early-stage transport networks with grants, setting the stage for broader capture and storage growth, as outlined by the DOE.

Bibliography

Energistyrelsen2024 “Technology Data for Carbon Capture, Transport and Storage”, Danish Energy Agency & Energinet

Technology catalogue that describes solutions that can capture, transport and store carbon. The catalogue covers various forms of carbon capture technologies for thermal plants and the industrial sector, as well as direct air capture, and contains different infrastructural solutions regarding CO₂ transport and storage. The catalogue also evaluates the development potential of those CCS technologies.