Land development for CO₂ hubs

Examining the process of developing a CO₂ hub with an industrial land development perspective, reconnecting us to the process and spirit of building.

This article, though very much a work in progress and somewhat enumerative, is my own view on a greenfield CO₂ hub development process based on my industrial land development experience and discussions with cryogenic engineers.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) 1 is a vital step in decarbonising heavy industry, and CO₂ hubs serve as key logistical nodes in a feasible and practical carbon transport and storage (CTS) 2 value chain. These hubs, whether designed as shared CO₂ capture and processing facilities or distribution terminals, require varying amounts of strategic land development to connect industrial emitters to offshore CO₂ storage wells or utilisation hubs. Particularly for greenfield 3 projects, securing and preparing suitable land is a significant challenge often overlooked in broader CCS discussions. Drawing on my land development roots, this hurdle stands out as a critical first step, adaptable to pre-zoned sites within ports, typically offered under a concessionary landlord model (Notteboom2022, p. 306).

Developing CO₂ hubs is an interdisciplinary affair involving commercial real estate, cryogenic engineering, supply chain management, and a regulatory maze that would test even Charles Dickens’ patience. Even conglomerates like Equinor get tested; for instance, one of their CO₂ pipeline projects got derailed by having to manually seek approval from two thousand private landowners (I know from first-hand sources). Given the novelty of CO₂ hubs, few have built them, yet CO₂ terminals like the Northern Lights and Porthos exemplify the possibilites. However, their development often falls to unknown corporations, distancing us from the excitement of creation.

Aside from the need for specialist engineering, I view CO₂ hubs as a frontier built on familiar site selection and infrastructure planning principles. Therefore, I’d like to “reconnect us to the process and spirit of building” (Zogolovitch2018) by offering a practical introduction to developing CO₂ hubs seen through a land development lens, paving the way for service-driven supply chains to meet decarbonisation demands. I’ll illustrate how aligning site selection, zoning, and front-end engineering design (FEED) with engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) provides a foundation for greenfield CO₂ hub development, while covering general regulatory, technical, financial, and operational considerations you must keep in mind during the process.

General process

The greatest danger lies not in ignorance, but in the false confidence of half-knowledge, which builds upon sand where rock is needed.

John Ruskin

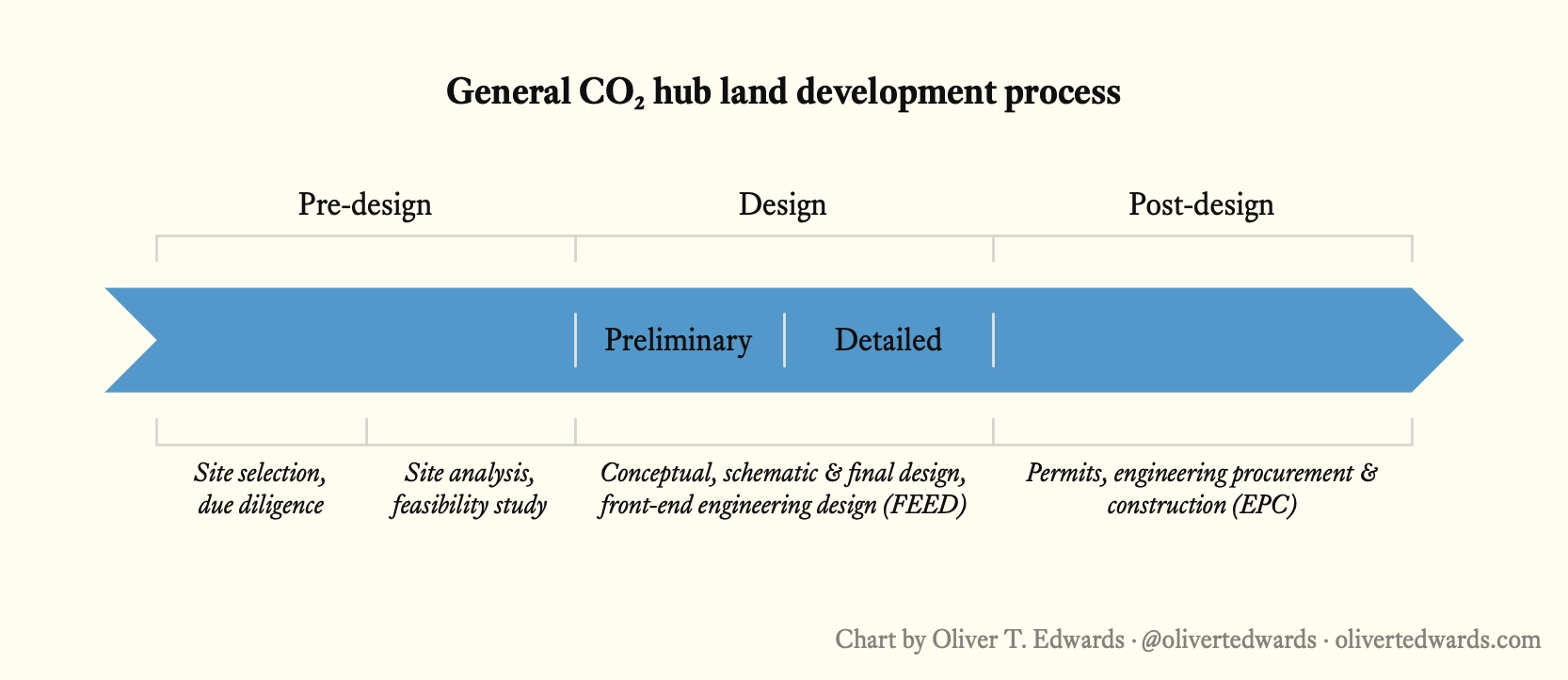

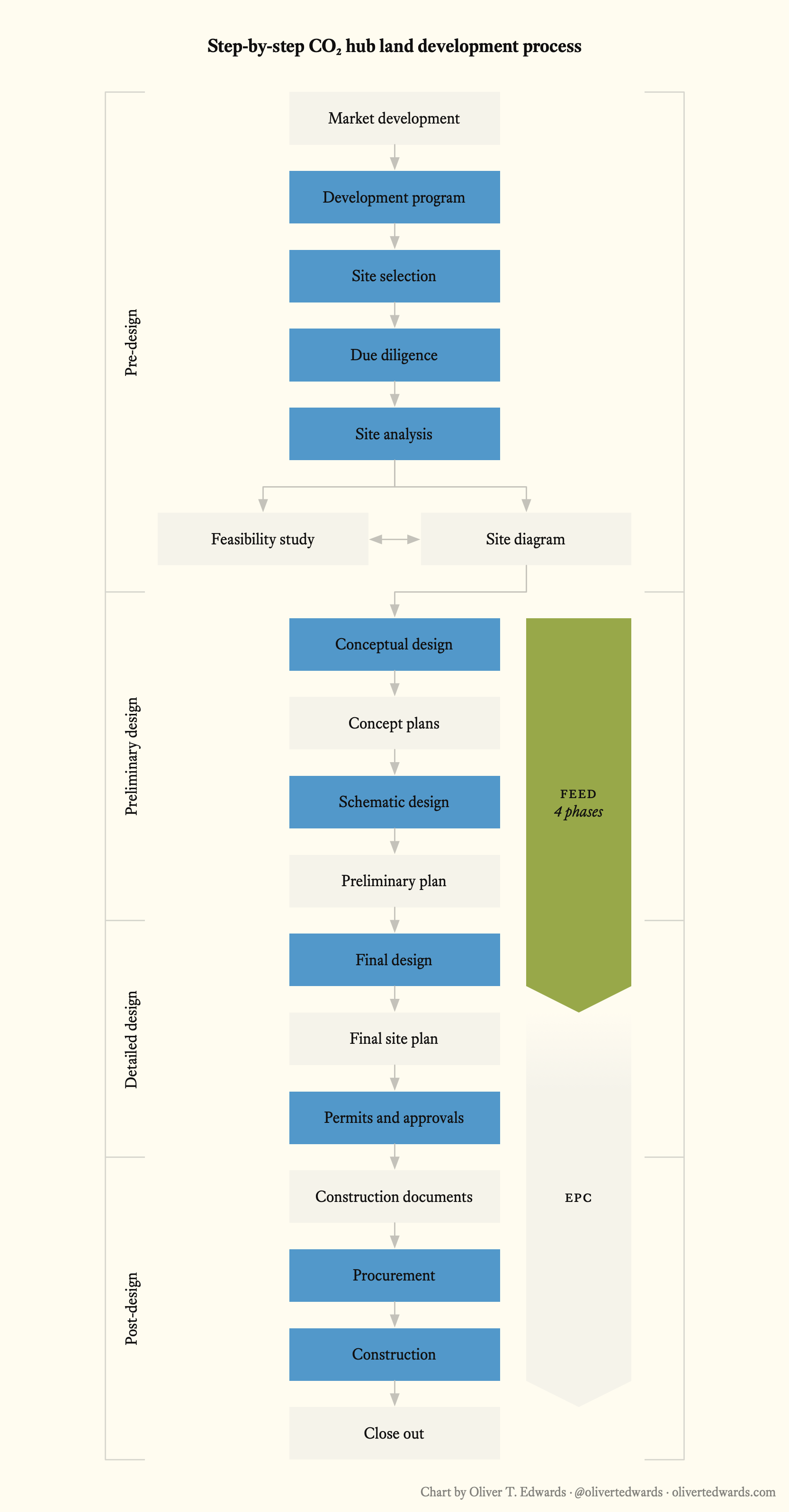

Developing a CO₂ hub on a greenfield site leans heavily on common land development methods, although their novelty demands specialist engineering across the preliminary design, detailed design, and post-design phases, where the front-end engineering design (FEED) 4, and engineering procurement & construction (EPC) 5 steps are embedded. However, before any design or construction can begin, we must first secure a feasible site; all of which happens in the pre-design phase.

CO₂ terminals also fall within the hub development category, though many port developers will argue that “special powers are required to bring forward any new harbour development” (Irving2019). Plots within a port are typically pre-zoned and offered under a concessionary landlord model, altering the development process considerably.

During the pre-design phase, we focus on exploratory efforts with minimal investment to determine if the project is feasible. Here we assess market demand, regulatory constraints, site conditions, and financial viability. Our design work begins with a preliminary design phase, focusing on conveying the project’s intent with simple design elements to aid internal discussions, early dialogue with consultants, landowners, and governing authorities. This is also the first step in anchoring technical specifications with process engineers to develop a conceptual and schematic design of the project before the next phase. In the detailed design phase, we expand on preliminary designs leading to a final design, focusing on engineering details that will help us finalize budgeting, permitting, and construction through refined site layouts, calculations, technical narratives, and specifications. Major changes may require revisiting earlier phases, making validation of prior work essential before advancing. Lastly, in the post-design phase, we execute the project and ensure operational readiness, including permitting, construction documents, procurement, construction, and closeout.

For many reasons, developing a harbour site is quite different from a residential area. One critical detail is that harbours are often partially or fully owned by public entities, such as a municipalities, making them key players (even team members) in hub development. Unlike private entities, public entities must prioritise public service over profit, while achieving regional sustainability goals and economic growth like job creation. Working with a good municipality is a huge advantage in getting things moving, though public entitity involvement also introduces some unique challenges: funding constraints, political will, and complex regulatory processes can delay or derail projects (Dewberry2019, p. 4). For instance, harbour developments must navigate municipal ownership dynamics, where elected officials’ support can shift due to citizen opposition, election cycles, or competing priorities like budget allocations for schools or roads. Public sector funding often relies on tax appropriations or bonds, requiring long-term budgetary planning that may not align with fluctuating construction costs, leading to potential shortfalls. Additionally, the regulatory landscape for CO₂ handling, spanning local zoning, environmental protection, and maritime transport laws, adds further layers of complexity, often necessitating compliance with overlapping standards. Public private partnerships (PPP) 6 are increasingly vital in this context, allowing private developers to finance and manage CO₂ hubs in collaboration with municipalities, reallocating risks and driving efficiencies in cost, time, and innovation to overcome public sector limitations.

Pre-design

The pre-design phase, often referred to as a feasibility study period, is about exploration with minimal upfront investment. It lays the groundwork by assessing whether a CO₂ hub is viable in a given region. Developers kick off with a development program, defining the hubs’s purpose (for instance a distribution or utilisation hub) and aligning it with regional goals, such as sustainability goals. This step involves scoping the market, identifying CO₂ emitters, and outlining economic and environmental benefits, setting a clear vision for the project. Next, site selection narrows the focus to potential locations, prioritizing sites near industrial emitters and with access to transport infrastructure like railways or pipelines. This stage often involves early negotiations with landowners or municipal authorities. Subsequently, due diligence means diving into market demand, regulatory landscapes, and economic feasibility. This includes engaging various stakeholders to identify risks and opportunities, such as zoning restrictions or public opposition. While the development team coordinates this process, specialised consultants are often brought in for legal, environmental, and financial assessments to ensure a thorough evaluation. Site analysis then evaluates the site’s physical conditions, from soil stability to harbour depth (if the hub is at a port, dredging might be needed to support the required vessel sized), ensuring it can support heavy infrastructure like CO₂ tanks. Finally, a feasibility study synthesises these findings into a go or no-go recommendation, shaping the strategies needed to move forward. This phase is critical for avoiding costly missteps, offering a solid foundation before design work begins.

Development program

The development program serves as the foundation for a CO₂ hub project, outlining our objectives and requirements, including the proposed use and design needs, which must be clearly communicated and understood by the entire team; often with valuable input from the design team due to their expertise. This initial framework guides all subsequent steps, though it may evolve with later design phases, where significant changes could impact the project’s schedule and budget, requiring careful management to maintain alignment with regional and national goals.

Site selection

Site selection is a critical step in CO₂ hub development, involving the careful choice of a suitable location from one or multiple potential sites, where the development team conducts due diligence across legal, financial, and site-based factors, while the site or process engineer assesses regulatory and physical aspects. This process lays the groundwork for identifying viable options that align with project needs. Preliminary environmental impact assessments (EIA) are conducted at this stage to identify potential environmental constraints early, ensuring compliance with local regulations and reducing risks down the line.

Due diligence

Due diligence is a comprehensive evaluation to assess market viability, regulatory compliance, site potential, and economic feasibility before major commitments. This involves reviewing regulations, the development program, local ordinances, and codes, followed by a preliminary desktop site review. Constraints and opportunities are identified, enabling an initial go or no-go decision for each site based on the development team’s findings. While the development team coordinates this process, external specialists (legal advisors, environmental experts, and financial analysts) are often engaged to ensure thorough assessments across these complex areas.

- Market analysis. Beginning with a market analysis allows us to generate critical regional supply and demand insights, enabling sound decision-making for a CO₂ hub project. This involves defining the target market, including CO₂ emitters and transport firms along with their specific needs, assessing supply and demand dynamics by examining existing hubs and regional trends, and analyzing competition based on nearby facilities, pricing, and capacity. Evaluating the competitive landscape, including existing CO₂ hubs and their capacities, is essential to understand market saturation and positioning. Projecting revenue potential through storage fees and absorption timing, while monitoring economic trends like carbon pricing and policy shifts, rounds out the process, with regular updates ensuring adaptability to evolving market conditions.

- Initial site assessment. Once a potential site is identified, the next step involves a basic evaluation of its physical conditions and regulatory status to determine an initial go or no-go decision, a critical early move in the pre-design phase. This process also assesses the landowner’s willingness to participate, while building trust as the project unfolds, though landowners might leverage increased property value, requiring careful negotiation. Their input, such as recent land title surveys, can prove invaluable, while for harbours, early engagement with municipal owners can unlock concession terms. The assessment blends physical traits (proximity to CO₂ emitters, infrastructure access) with legal factors (zoning, easements), offering a foundation for pricing and planning.

- Economic feasibility. Determining whether a CO₂ hub project will pencil out requires a robust financial assessment, starting with a cash flow analysis to balance fees against costs, alongside evaluations of land prices, development timelines, and revenue potential from transport and storage contracts. This process involves calculating development costs (tanks, pipelines, permits) and soft costs (consultancy, legal), while considering loan and value ratios, lending guidelines, and the availability of financing options. Municipal requirements, such as performance guarantees or grants, and comprehensive documentation like pro forma statements further shape this feasibility.

- Stakeholder engagement strategy. Building a CO₂ hub requires a thoughtful approach to engaging key stakeholders (regulators, CO₂ suppliers, and community groups) to ensure project success and community buy-in. This involves assessing local sentiment toward CO₂ projects, addressing concerns about safety and environmental impact, and identifying potential regulatory hurdles like delays in storage permitting early on. A structured plan for consultations, including public meetings and workshops, alongside a clear outline for regulatory engagement covering permit timelines and compliance, helps navigate these challenges. Establishing ongoing communication channels keeps stakeholders informed.

Site analysis

Site analysis, part of due diligence, evaluates a site’s physical conditions, focusing on environmental, cultural, and infrastructure elements to pinpoint opportunities and constraints, potentially requiring plan changes or a new site. It yields a site inventory, defines usable areas, and provides base mapping for design, aiding in the creation of the feasibility study and site diagram. At this stage, we might have onboarded the landowner, which can make further analysis a lot easier.

- Site constraints and opportunities. Still interested in the site after the initial assessment? A deeper analysis is essential to evaluate its physical conditions, environmental factors, and regulatory implications, ensuring it can support a CO₂ hubs’s infrastructure. This involves conducting a land title survey, walking the property to document features like topography, wetlands, and cultural resources, and assessing potential constraints such as poor soils, geological hazards, or limited access for CO₂ transport, while also identifying opportunities like existing utilities or harbour proximity. Additional investigations into environmental impacts, utility capacity, and cost implications (foundation reinforcements) further refine the site’s suitability.

- Government constraints and opportunities. What can be done on the property depends heavily on understanding the local regulatory landscape, a key step in assessing its suitability for a CO₂ hub. This involves reviewing the community’s development approval procedures, gauging local attitudes toward new projects, and examining existing plans (such as comprehensive or growth management plans) to align with the future vision for the area. Key considerations include understanding zoning laws, which dictate allowable land uses and restrictions, and the permitting process, which can significantly impact project timelines due to reviews and approvals. Additionally, it’s important to confirm whether the property’s zoning supports industrial use, while also noting any overlay districts or requirements like land donations or inclusionary zoning.

Feasibility study

The feasibility study integrates market, regulatory, technical, and economic data into a formal report, culminating in strategies for financing and land acquisition to finalise the go or no-go decision. A critical step in this process is conducting a risk assessment to identify potential challenges (regulatory delays, cost overruns, or technical failures) and outlining mitigation strategies like contingency plans or additional studies to address them.

- Financing strategy. Securing funding for a CO₂ hub demands a detailed plan that builds on the economic feasibility assessment, ensuring the project’s financial viability. This involves identifying appropriate funding sources tailored to project needs, exploring CO₂-specific incentives like CCS grants or carbon credit programs, and finalising loan and value ratios to align with lender requirements. Securing municipal financing options, preparing comprehensive documentation such as pro forma statements and cost estimates for lenders, and confirming performance guarantees to meet municipal standards are critical steps. Updating financial projections with refined cost estimates from site analysis further strengthens the plan.

- Land acquisition strategy. Planning the acquisition or leasing of a chosen site for a CO₂ hub requires careful alignment with budget and legal constraints to ensure a smooth transition to development. This involves preparing to finalize a land purchase contract or negotiating a harbour lease/concession agreement, confirming budget availability based on economic feasibility, and addressing legal hurdles identified during due diligence, such as easements or title issues. Converting early discussions into binding agreements (such as those with emitters or port authorities) while planning for contingencies like renegotiation due to new constraints, is essential. Securing necessary approvals for land use, including zoning changes or port concessions, completes the process.

Site diagram

The site diagram, an initial graphical depiction of proposed site conditions, is drawn on the base map to illustrate geographic relationships using data from site analysis and due diligence, serving as a vital foundation as we transition into the design phase with process engineers. This step consolidates key insights to guide the project forward.

Preliminary design

The design phase transforms the pre-design vision into a detailed blueprint, alongside FEED as the engineering cornerstone. The preliminary design phase initiates this process, beginning with conceptual design. Here, engineers sketch initial layouts for CO₂ storage tanks, loading docks, and pipeline routes, ensuring alignment with safety regulations and scalability for future expansion. These concepts evolve into concept plans, offering multiple layout options for stakeholder review, often sparking informal discussions with port authorities or local agencies.

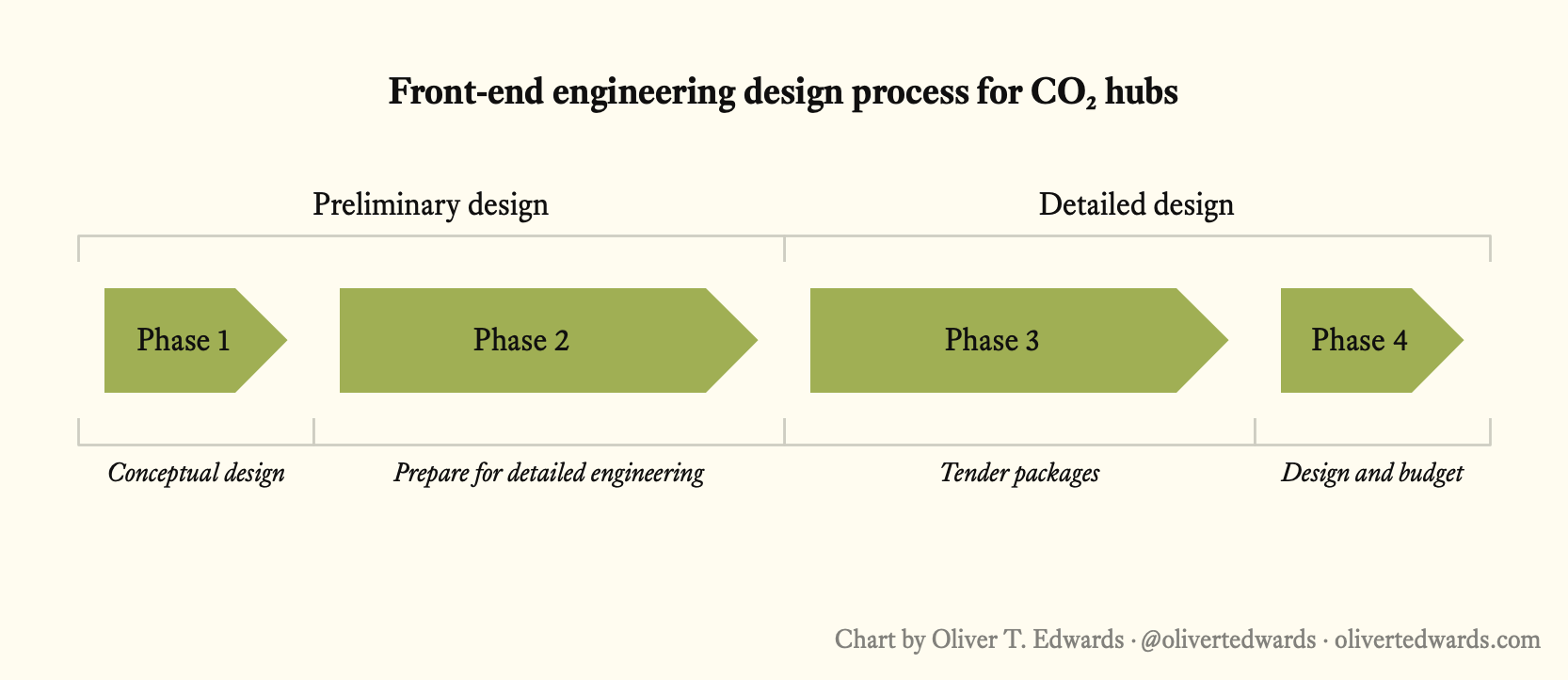

Front-end engineering design (FEED) 4 serves as the technical cornerstone of the design phase, a structured engineering process with four sub-phases that begins in sync with conceptual design, refines the layout to enable schematic design, and provides outputs that feed into the detailed design phase. This critical process ensures a solid foundation for the project.

Conceptual design

Conceptual design begins with the site diagram from the pre-design phase, aiming to establish a preliminary framework for the development program’s layout by respecting constraints and capitalizing on opportunities identified through due diligence and site analysis, with the resulting concept plans offering multiple alternatives for land use and infrastructure arrangements tailored to program and site needs for developer review or informal stakeholder discussions. This process lays the groundwork for a preliminary plan, a 30% complete design package used for formal submissions like rezoning or special permits, with FEED’s technical outputs providing a foundation for the subsequent detailed design phase.

Schematic design

Schematic design refines the preferred concept plan, leveraging FEED’s technical refinements to provide precise scale and site details based on due diligence and site analysis, while including a site layout that aligns with client goals and regulatory requirements. This phase builds on the conceptual design by adding specific details, such as equipment placement, material considerations, and compliance with local regulations, ensuring a clearer path to feasibility. Preliminary engineering verifies technical aspects, producing graphics and reports as a final check before detailed design, playing a crucial role in estimating costs and verifying feasibility (representing about 30% of the final design effort with expected modifications) and offering greater detail for formal submissions.

Detailed design

The detailed design phase builds on the preliminary design phase’s FEED outputs, marking a pivotal transition as the project moves toward construction readiness. Early FEED work (piping diagrams and equipment specifications) continues to run alongside this phase, refining technical details, while the process sets the stage for EPC to begin overlapping, particularly as permitting processes gain momentum. This integration ensures a seamless flow from design to execution.

Final design

Engineers transform the schematic design into a comprehensive final design, delivering the precision required for construction and permit approval by local agencies through preliminary reviews and iterations, with the building design team potentially adjusting architecture to support infrastructure elements like CO₂ storage tanks or pipeline routes. The resulting final site plan, a culmination of these efforts, is submitted for regulatory review and permitting, serving as the blueprint for construction once approved, while leveraging FEED’s technical foundation to initiate the transition to EPC alongside permitting. As EPC activities often begin during the final design phase, particularly as permitting advances, this overlap ensures procurement and construction planning are aligned with design completion, streamlining the transition.

Permits and approvals

Permitting is a crucial step that involves obtaining all necessary site and building permits, including a final site plan, before construction of a CO₂ hub can begin, encompassing a range of approvals for demolition, land disturbance, transportation, environmental conditions, and building construction, often requiring project bonds and legal agreements. This process ensures compliance and community support.

Post-design

The post-design phase turns plans into reality, marking the shift from design to execution alongside the EPC process. Permits and approvals leverage FEED’s budgets and approvals to secure CO₂ specific permits, such as environmental, storage, and transport authorisations, often requiring public hearings to address community concerns like leak risks. Construction documents then detail safety specifications and harbour berth requirements, translating FEED designs into actionable blueprints. Procurement uses FEED tender packages to purchase critical equipment, such as CO₂ tanks and pipelines, setting the stage for construction. Throughout this phase, construction management and quality control are essential to ensure the hub is built as designed, with rigorous oversight and inspections, while commissioning verifies operational readiness through testing and validation.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a process by which carbon dioxide (CO₂) from industrial installations is separated before it is released into the atmosphere, then transported to a long-term storage location. ↩︎

Carbon transport and storage (CTS) is the infrastructural and logistical link enabling the carbon capture and storage (CCS) value chain to function. ↩︎

In real estate, a greenfield refers to undeveloped land in a rural or suburban area that has not been previously built upon or developed for a specific purpose, offering a “clean slate” for new development projects, such as residential, commercial, or industrial construction. ↩︎

Front end enginnering design (FEED); process for conceptual development of projects in processing industries such as upstream oil and gas, petrochemical, natural gas refining, extractive metallurgy, waste-to-energy, biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals, involving developing sufficient strategic information with which owners can address risk and make decisions to commit resources in order to maximize the potential for success. ↩︎ ↩︎

Engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC); form of contract used to undertake construction works by the private sector on large-scale and complex infrastructure projects, often following a front-end engineering and design (FEED) contract. ↩︎

Public-private partnerships (PPP, 3P, or P3) are a long-term arrangement between a government and private sector institutions. Typically, private capital finances government projects or services up-front, then draws revenue from taxpayers or users for profit during the course of the contract. ↩︎

Bibliography

Zogolovitch2018 “Shouldn’t We All Be Developers?”, Solidspace

Shouldn’t we all be developers’ articulates Roger Zogolovitch’s vision for recognition of the independent and creative developer playing their part to generate supply of new homes in the UK and beyond to meet population demand. Housing as a human right is the premise.

Notteboom2022 “Port Economics, Management and Policy”, Routledge

Port Economics, Management, and Policy (PEMP) analyses the contemporary port industry and how ports are organised to serve the global economy and regional and local development needs. It uses a conceptual background supported by extensive fieldwork and empirical observations, such as analysing flows, ports, and the strategies and policies articulating their dynamics. The port industry is comprehensively investigated in this unique compilation.

Irving2019 “Harbour Development: A Practical Guide”, Winckworth Sherwood

A practical introduction to the process of authorisation of port or harbour schemes in England. It is aimed at potential developers and/or consultants who are new to the subject and outlines the permissions required, as well as some of the issues to be considered, when bringing forward a scheme that includes a harbour. The note focuses on applications for orders under the Harbours Act 1964 (“the 1964 Act”), which remains the relevant consenting process for any port and harbour developments (including marinas) that do not meet one of the thresholds for nationally significant infrastructure. The note also mentions some relevant policy matters that potential developers should be aware of. Finally, it describes the key skill-sets that will be required in the project team in order to put together a compliant application.

Dewberry2019 “Land Development Handbook”, Dewberry

This thoroughly revised resource lays out step-by-step approaches, from feasibility through design and into permitting stages of land development projects. Land Development Handbook, Fourth Edition, offers a holistic view of the land development process for public and private project types—including residential, commercial, mixed-use, and institutional. The book contains the latest information on green technologies and environmentally conscious design methods. Detailed technical appendices, revised graphics, and case studies round out the content included.