Zero-carbon shipping for CCS

Fossil-fueled ships are quietly gutting CCS budgets with EU ETS fees and lost credits, but multi-fuel vessels can bridge the transition into green shipping to remove the losses.

Originally published as a subscriber article in the Carbon Capture Journal (issue 101), a leading magazine for carbon capture storage and utilisation, and subsequently presented at the Zero Emissions Platform, the official EU advisor on industrial carbon management.

While CCS 1 is a key technology for decarbonising industry, scaling it to handle 40 gigatonnes each year is a massive logistics challenge facing inadequate transport and hub infrastructure. The global fleet of CO₂ carriers 2 also needs to be expanded dramatically 3 to manage such volumes. Yet, as carbon taxes rise, building new fossil-fuelled vessels is a path that ironically incurs high EU ETS emissions costs for transporting CO₂ while diminishing the carbon credits of biogenic emitters. So, this path ultimately ruins CCS budgets, and I know a good handful of emitters who are very concerned.

Ammonia-powered ships, supported by multi-fuel designs, present a practical zero-carbon solution to this dilemma. They’re expensive, but a well-crafted capital structure can mitigate the commercial and financial risks tied to their rollout.

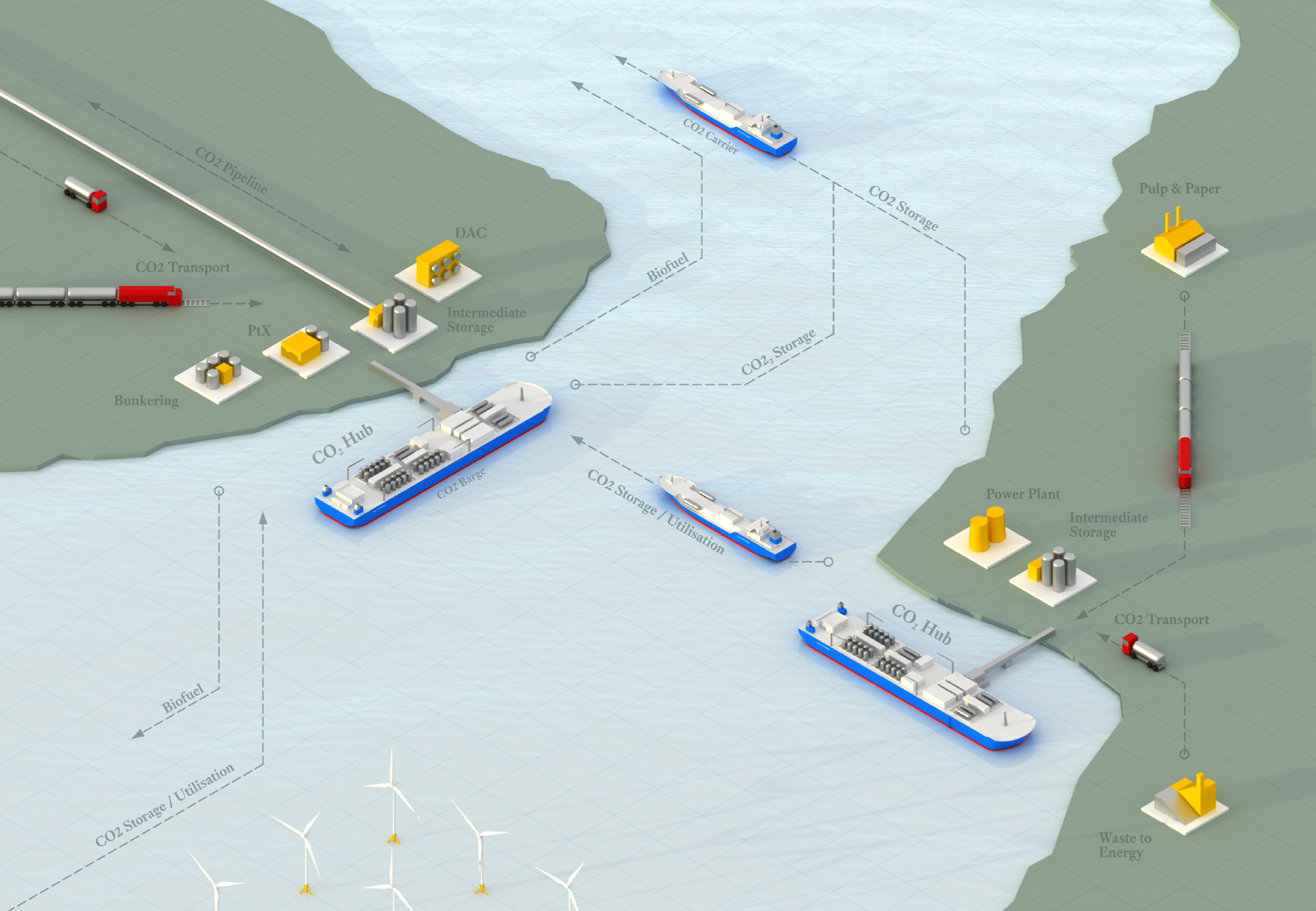

Carbon gigalogistics

Scaling CCS is a logistical nightmare, overshadowed by the unfathomable volume of global CO₂ emissions: 40 gigatonnes 4 from burning fossil fuels in 2022—enough to cover Alaska, Texas, and California under eight meters of gas (Tso2023). The EU wants to capture 250 megatonnes a year by 2050, but CCS is pointless without transport infrastructure that can handle CO₂ volumes at megatonne-scale. Commercial transport and storage value chains are maturing with the Northern Lights capable of handling 1.5 megatonnes per year, but its shipping slots are fully booked, leaving emitters stranded. I’ve heard plant managers gasp when they realise the lack of transport options kills their capture projects. Pipelines sound promising, but they can’t reach everywhere, and the long lead times and high upfront investment costs make their deployment impractical—ships are a necessary piece of the puzzle (Lockwood2025). However, a typical carrier hauling 10-25 kilotonnes of liquefied CO₂ per trip is barely a dent in 40 gigatonnes, and retrofitting current fleets won’t solve capacity needs either. 5 A new fleet of carrier ships is needed for increasing global CO₂ shipping capacity.

Dirty ships kill CCS budgets

Despite needing to expand the CO₂ carrier fleet, building more fossil-fuelled ships is a trap that can ruin emitter budgets with taxes and credit losses, especially on long-distance routes. Under the EU ETS, cargo ships above 5,000 gross tonnage 6 must surrender EUAs 7 for 70% of their CO₂ emissions, increasing to 100% from 2026. With EUA prices projected at €100/t in 2027, a CO₂ carrier burning MGO 8 on a 550 nautical mile 9 transit from Belgium to the Northern Lights terminal, emitting roughly 0.5 tCO₂/nm, 10 would cost €19,250 in EU ETS costs at the 70% rate. Northern Lights has opted for LNG-fueled ships (0.32 tCO₂/nm) which could reduce the cost by 21% (Istrate2022, p. 76), but even that is not nearly enough to reach the IMO 50% greenhouse gas reduction target by 2050. Keeping transport costs low is critical because CO₂ management is more akin to low-margin waste management than the high-margin oil business. So, these numbers scare plant managers, and for good reason, because the cost is ultimately passed onto them as shipping companies increase the tonne-mile price 11 they offer their customers. Worse still, for biogenic emitters, CO₂ emitted during transport subtracts from the negated emissions ledger (the net CO₂ removed after accounting for lifecycle emissions), lowering their ability to sell carbon credits, reducing their ROI on CCS. This highlights the urgent need for zero-carbon fuels like hydrogen or ammonia, because even purpose-built CO₂ carriers running on fossil-fuels will drain CCS budgets, stunting decarbonisation efforts.

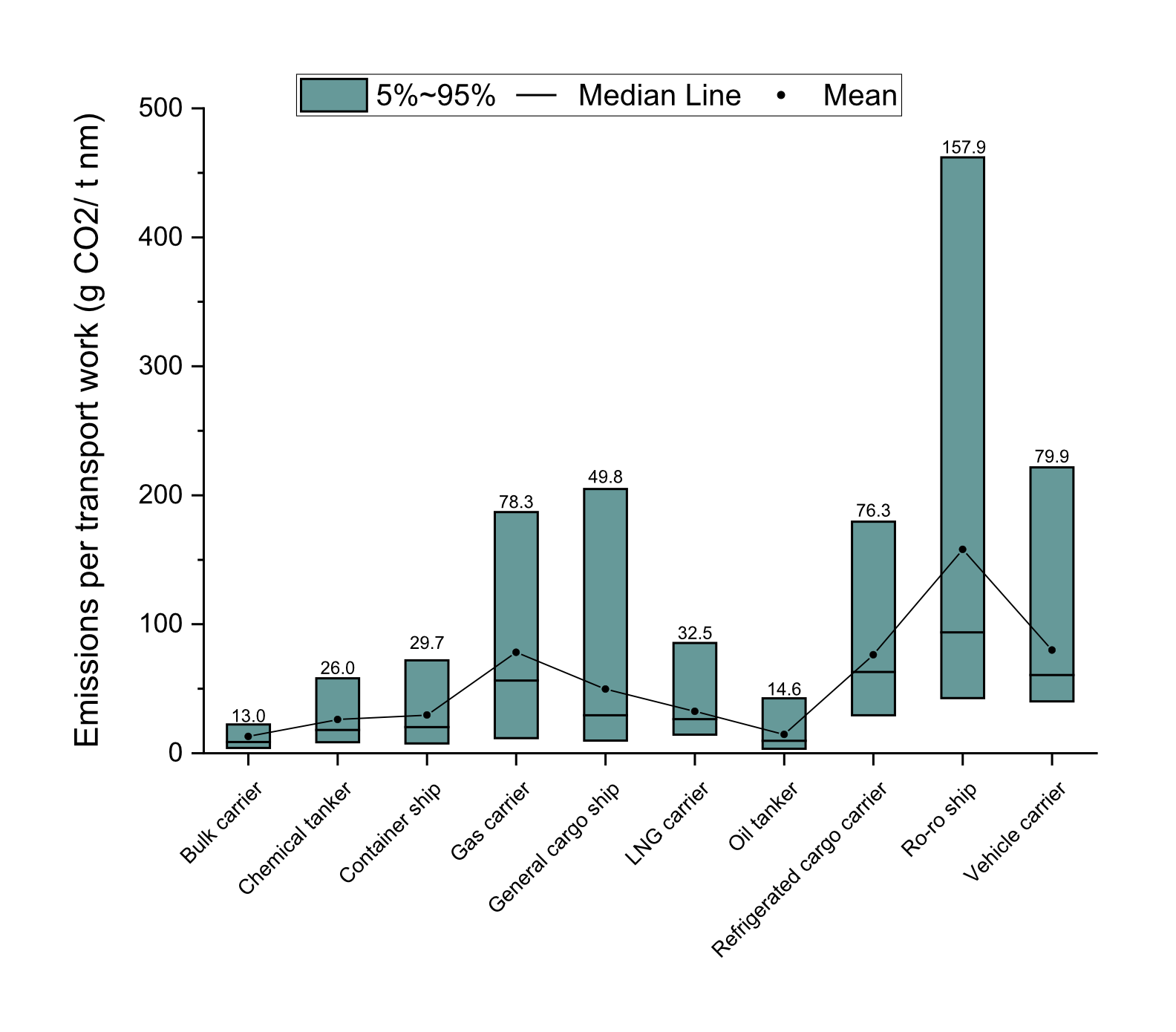

Emissions from fossil-fueled ships vary widely across vessel categories, which is important to keep in mind when calculating the financial strain on CCS projects. From 16.4 g CO₂/t·nm for bulk carriers to 158 g CO₂/t·nm for ro-ro ships, oil tankers at 20 g CO₂/t·nm, and chemical tankers at 26 g CO₂/t·nm (Istrate2022). These figures, based on 2019 THETIS-MRV data, reveal that less efficient ships like ro-ro vessels emit nearly ten times more per ton transported than bulk carriers, driving up EU ETS costs for operators reliant on MGO or LNG. An IMO report (Faber2020) underscores that such inefficiencies, coupled with projected emission increases of 90–130% by 2050, necessitate a swift shift to zero-emission fuels like ammonia to protect CCS budgets and meet decarbonisation goals in general. Given these developments, I wouldn’t be surprised by Bloomberg’s EU ETS price projections at €149 by 2030, further increasing shipping costs.

Ammonia as a shipping fuel

Ammonia is a scalable zero-carbon fuel that is suitable for serving long-distance shipping routes. Its adoption in maritime transport ensures that CO₂ captured from emitters can be moved to storage sites without emitting additional CO₂, aligning perfectly with CCS objectives. Ammonia-powered vessel designs are generally deemed mature for deployment. However, deployment is a challenge because ammonia vessels are 50-130% more expensive than conventional ships due to their novelty, and the economic risks of building a global ammonia-fuel network (Boyland2022). With limited capital support, widespread deployment will take time, which creates uncertainty around the practical costs of CO₂ transport for both shipowners and emitters. These logistical uncertainties cause delays in deploying CCS at scale. It also increases the overall cost of CCS to a degree where industrial emitters can loose their incentive to implement CCS despite the significant carbon taxes imposed on their operations.

How can we enhance the willingness of institutional investors to provide capital support for these projects and strengthen the case for quickly rolling out CO₂ transport, ensuring that transport infrastructure does not become a bottleneck?

Commercial deployment barriers

Deploying ammonia ships is costly due to the need for specialised fuel infrastructure making it significantly more expensive than traditional marine fuels. This creates commercial risks in the form of:

- Market risk: Shipowners bear the initial cost of adopting more expensive fuel technology, with uncertain returns on investment.

- Credit risk: Financiers are cautious about the long-term viability and profitability of ammonia-powered ships, given their higher operational costs.

- Infrastructure risk: The lack of a comprehensive fueling network for ammonia adds uncertainty to operational planning and cost structures.

- Technology risk: Unforeseen technical issues or advancement of newer and more efficient designs could render current work obsolete.

The high costs associated with ammonia as a marine fuel stem from several factors:

- Lower energy density: Ammonia’s lower energy density requires larger fuel storage on ships and on land, increasing design complexity and capital costs.

- Advanced engine technology: Developing engines that efficiently use ammonia necessitates heavy investment in research, testing, and certification, adding to the cost burden.

- Safety equipment: Ammonia’s toxicity and corrosiveness demand specialised safety systems for storage, handling, and fuelling, further driving up costs.

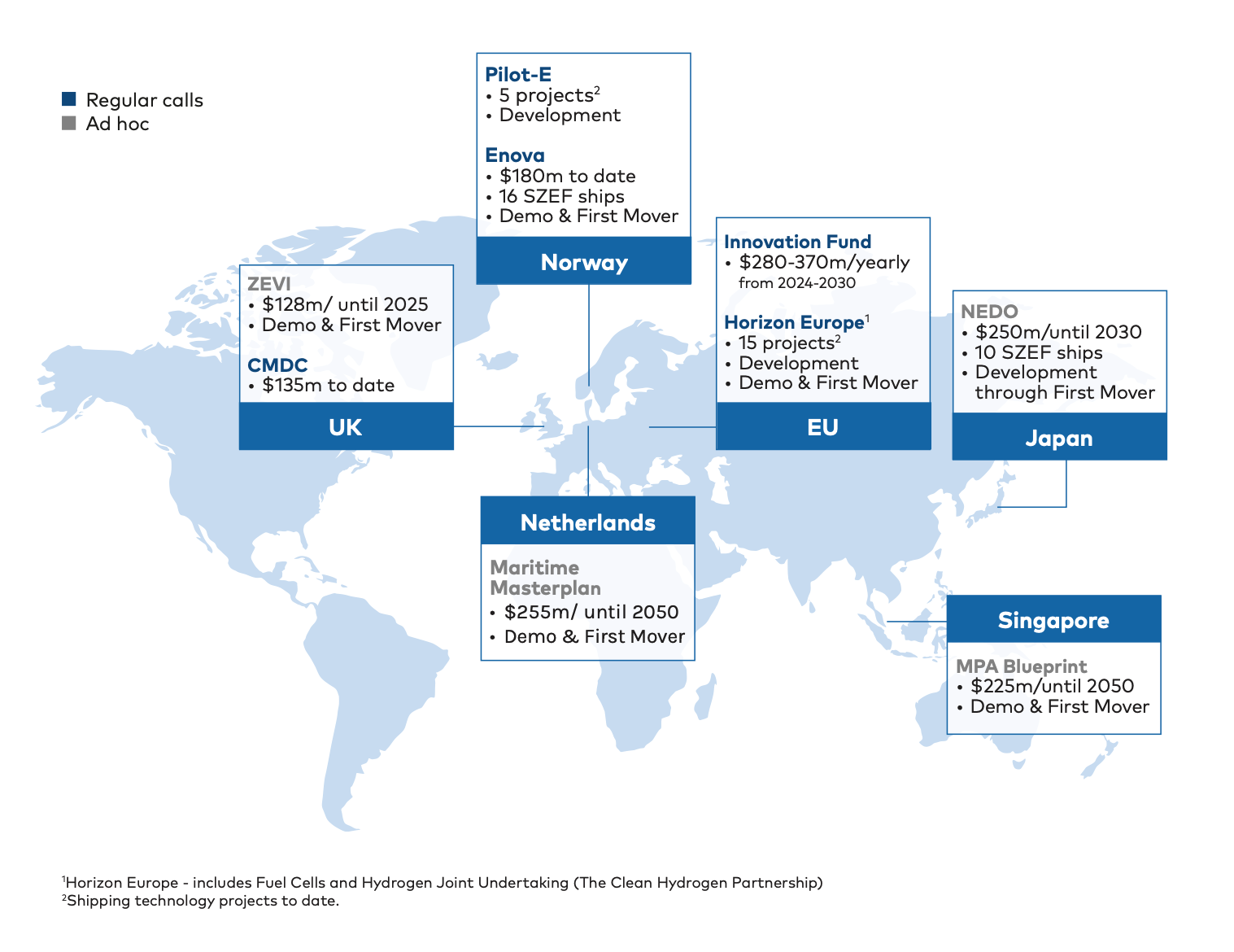

Funding green ships

Currently, the maritime industry’s shift towards ammonia as a fuel source is met with cautious optimism but also with financial hesitancy. Public grants and subsidies (often the lifeblood of innovation in critical infrastructure) are primarily focused on research and development rather than widespread deployment (Boyland2022).

This gap in funding underscores a critical challenge: while the technology for ammonia-powered vessels exists, the economic framework to support their commercial rollout is still in nascent stages.

Multi-fuel ships as a bridge

Given limited capital support and stricter emission regulation, shipowners have sought out solutions for de-risking the transition for themselves, solutions such as multi-fuel engines that can use both conventional fuel and ammonia, which lowers the risks and immediate costs associated with transitioning to ammonia fuel. That means they can run the ships purely on ammonia when the fuel network is ready.

Recently, the Norwegian shipowner, Höegh Autoliners, took delivery of 1 of 12 new ammonia and methanol certified pure truck and car carrier ships (PTCT) in China. Not only is this a significant investment, but when such an industry heavy weight commits to such an order, it not only reduces their own risk during the transition, it signals to the remaining industry that we’re nearing the time to drive capital into global ammonia fuel infrastructure. The fact that Höegh Autoliners has invested so heavily in innovative fuel solutions is not just about compliance, but about setting new standards. With sustainability as a key investment criterion, these initiatives are likely help attract more capital, driving further innovation and adoption. Multi-fuel ships are a platform for bridging the risk of the transition, while sustainable fuel infrastructure is being scaled up and costs go down.

Capital structures

Achieving commercial viability for ammonia-powered ships requires significant investment, particularly in developing a global ammonia fuel network. Institutional investors must play a central role in this process because deep-sea shipping is integral to the global economy. By pooling resources, these investors can collectively lower the costs of developing the necessary fuel production and distribution infrastructure, making large-scale adoption feasible. However, institutional investment hinges on several factors. For one, investors must see a clear path to profitability, which includes ensuring that the infrastructure for ammonia is robust and that ammonia-powered ships themselves are financially viable. The Nordic Green Ammonia Powered Ships project proposes four key levers to reduce financial burned on shipowners and lower risks for institutional investors (Boyland2022).

- Cost-efficient, dual-fuel vessel design: This lever (reflecting our previous multi-fuel ship examples) focuses on minimising both capital and operational costs while mitigating residual value risks (depreciation of asset values like ships). Dual-fuel engines allow vessels to switch between conventional and ammonia fuels to make them adaptable to a developing market.

- Competitive financing arrangements: Securing cost-effective financing is crucial for the business case of ammonia-powered ships. This includes traditional bank loans and sustainability-linked loans, where interest rates decrease if environmental targets are met.

- Public sector de-risking measures: Governments can play a significant role by offering capital expenditure (CAPEX) grants and export credit guarantees, which directly reduce the financial burden on shipowners and make investments in ammonia-powered vessels more attractive.

- Premium long-term charter agreements: Securing long-term contracts with reputable charterers provides stable revenue streams, reducing credit and residual value risks for lenders and investors.

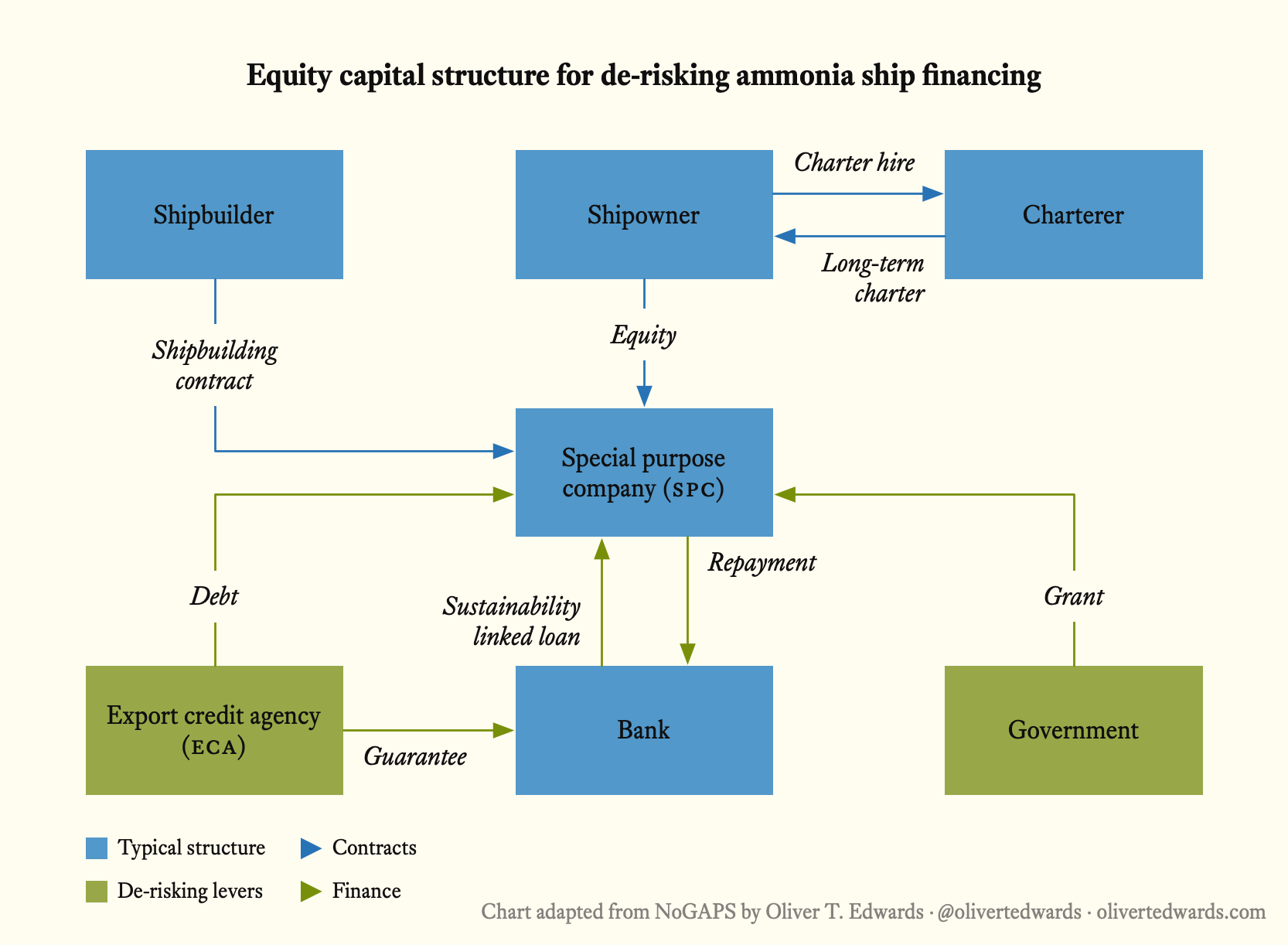

How do these levers work in practice? Let’s look at two capital structures proposed by the NoGAPS project for deploying ammonia-powered ships.

Equity model

In our first example, the ship is owned by a special purpose company (SPC), a legal entity created solely for owning and operating the vessel. The SPC utilises funds to secure a shipbuilding contract to ensure construction. This structure is designed to manage the risks associated with deploying new technology while providing sufficient capital to bring the vessel to market.

- Equity from the shipowner: The shipowner provides a significant portion of the equity, which is crucial for securing additional financing.

- Sustainability-linked loan: A bank offers a loan to the SPC, tied to specific sustainability targets. Meeting these targets could result in improved loan terms, reflecting the ship’s lower environmental impact.

- Government grant: A government grant helps offset the high initial costs associated with building an ammonia-powered ship, bridging the cost gap between traditional and zero-emission vessels.

- Debt or loan guarantee from an export credit agency (ECA): An ECA provides a guarantee for the loan, reducing the financial risk for the bank and encouraging investment by securing more favourable loan terms.

- Long-term charter agreement: The shipowner secures a long-term charter agreement, which provides stable revenue but can be challenging due to the costs associated with ammonia-powered ships.

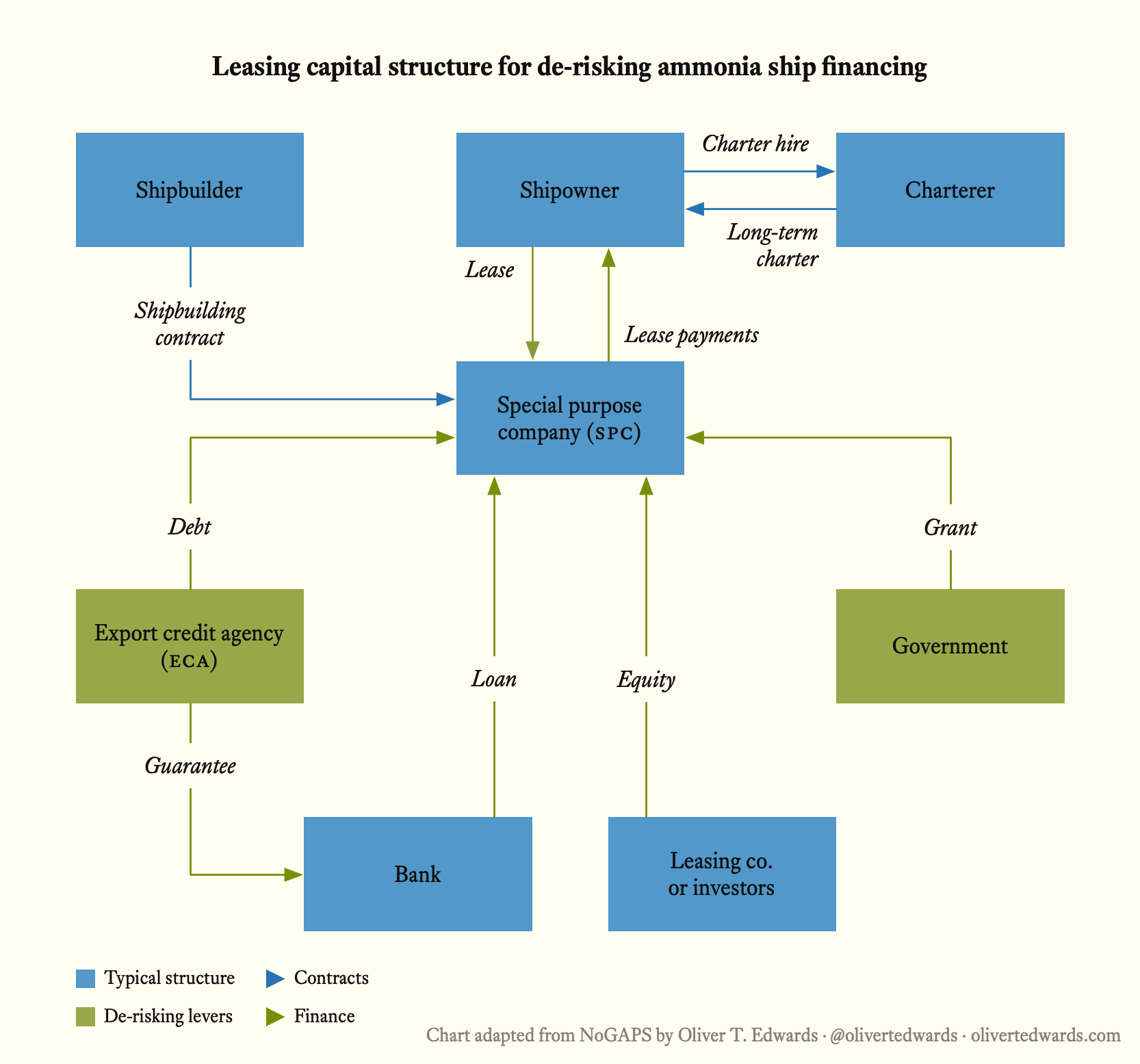

Leasing model

Our second example presents a leasing capital structure, designed to reduce the upfront capital requirements for the shipowner and mitigate risk during the transition.

- Equity from investors/leasing companies: Unlike the previous model, equity is provided by a group of investors or leasing companies, which spreads the risk across multiple parties. This equity, combined with contributions from the shipowner, is directed to the SPC.

- Bank loan: A bank provides a loan to the SPC, similar to the previous model, but this time the loan is directly associated with the leasing arrangement.

- Government grant and ECA guarantee: As in the first model, a government grant and a loan guarantee from an ECA are crucial to reducing financial risks and securing more favorable loan terms.

- Leasing agreement with the SPC: The ship operator enters into a leasing agreement with the SPC. This arrangement allows the operator to use the vessel without the need for significant upfront capital investment, making it an attractive option for operators who are cautious about the financial risks of new technology.

- Long-term charter agreement: As in the previous model, the operator also secures a long-term charter agreement with a charterer, providing stable cash flow and further reducing the financial risk.

Market maturity

The maritime sector’s move toward ammonia as a zero-carbon fuel is not just an environmental milestone; it’s a foundation for advancing CCS. As of late 2024, Clarksons reported a combined ammonia-ready fleet and orderbook of about 430 ships, and the Viking Energy was slated to become the world’s first ammonia-powered offshore support vessel by 2026.

These developments highlight both technological readiness and a general commitment to reducing emissions through new fuel solutions. The inclusion of shipping under the EU ETS as of 2025, alongside the FuelEU Maritime regulation’s push for lower GHG intensity in ship fuels, will continue to drive the adoption of ammonia, contributing to CCS advancement by:

- Accelerating infrastructure development, which will also support CO₂ transport and storage.

- Stabilising or reducing transport costs for CCS, making it more financially viable.

- Encouraging long-term carbon management projects through predictable costs and operations.

Scaling CCS to handle 40 gigatonnes of annual CO₂ emissions is a brutal challenge, exacerbated by the high EU ETS costs of fossil-fueled ships, and their impact on biogenic emitters’ carbon credits. Multi-fuel ships, like Höegh Autoliners’ ammonia-ready carriers, bridge the transition to zero-emission fuels, with 430 ammonia-ready hulls signaling market readiness as of 2024. However, deployment risks and funding gaps remain, requiring robust capital structures—equity and leasing models—and global bunkering networks to reduce costs. Institutional investors need to get onboard, leveraging public de-risking measures and long-term charters, to ensure maritime transport doesn’t bottleneck CCS.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a process by which carbon dioxide (CO2) from industrial installations is separated before it is released into the atmosphere, then transported to a long-term storage location. ↩︎

The global fleet of CO₂ carriers in commercial operation is three as of December the 4th, 2025. ↩︎

A typical carrier can haul 10-25 kilotonnes of liquefied CO₂ per trip, barely a dent in 40 gigatonnes, so retrofitting old vessels won’t solve capacity needs. ↩︎

Metric tonnes; 1 gigatonne (Gt) is 1,000,000,000 tonnes, 1 megatonne (Mt) is 1,000,000 tonnes, and 1 kilotonne (Kt) is 1,000 tonnes. Though fairly comparable, a metric ton is 2,204.6 lbs, which is a little more than the American ton’s 2,000 lbs and a little less than the British ton’s 2,240 lbs. ↩︎

Rough guestimate; the global LNG tanker fleet consisted of 772 ships in 2023, including FSRUs. Assuming each ship has a carrying capacity of 10–25 kilotonnes of CO2 the fleet could theoretically hold between 7,720 and 19,300 kilotonnes. In this case, LNG carriers would need retrofitted for CO2 transport since LNG has different density, storage, and operational contraints. ↩︎

Gross tonnage (GT) is a measure of a ship’s overall internal volume, used to determine the size of a vessel for regulatory and commercial purposes. Under the EU ETS, the obligation to surrender EUAs for CO2 emissions applies to cargo and passenger ships with a gross tonnage above 5,000, targeting larger vessels with a significant environmental impact due to their size and fuel consumption. ↩︎

EU Allowances (EUAs) represent an allowance to emit 1 tonne of CO₂ each, and they are traded as futures on platforms like the European Energy Exchange (EEX). In practice, for maritime operators, the cost of purchasing EUAs to cover emissions under the EU ETS can function like a pre-purchased tax on CO₂ emissions. ↩︎

Marine gasoil (MGO) and heavy fuel oil (HFO) are two common marine fuels with different compositions, properties, and applications. HFO is a residual fuel, meaning it’s the heavier byproduct of crude oil distillation after lighter fractions like MGO have been removed. MGO, on the other hand, is a distillate fuel, meaning it’s a lighter, more refined fraction of crude oil. ↩︎

Nautical miles; 1 nautical mile (nm) is 1.852 kilometers (km). ↩︎

MGO as a tanker fuel generally seems to emit around 0.5 tonnes of CO₂ per nautical mile supported by Istrate (2022), and our internally acquired research at Normod Carbon. ↩︎

Tonne-mile price; the cost charged by shipping companies per tonne of cargo transported per nautical mile, reflecting operational and regulatory expenses like EU ETS costs. ↩︎

Bibliography

Tso2023 “How much is a ton of carbon dioxide?”, MIT Office of Sustainability

In 2022, human activities emitted over 40 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere, primarily from burning fossil fuels. A single metric ton of CO2 occupies a 27’ x 27’ x 27’ cube, equivalent to the weight of a great white shark or 400 bricks. The average American generates 15 tons annually, enough to fill over three Olympic-sized swimming pools. Everyday activities like driving (4.6 tons per year for a typical car) and air travel (1 ton per 3,000-mile round-trip flight) contribute significantly, alongside food production (2 tons per person annually). Large-scale processes, such as electricity generation and steel manufacturing (nearly 2 tons of CO2 per ton of steel), dominate emissions. Switching to electric vehicles can reduce emissions to 22% of a gas car’s output. Globally, 40 billion tons of CO2 would cover Alaska, Texas, and California to a depth of 27 feet, underscoring the scale of emissions.

Lockwood2025 “Building Future-Proof CO2 Transport Infrastructure in Europe”, Clean Air Task Force

The European Union’s net-zero emissions goal by 2050 requires large-scale CO2 capture and storage to decarbonize industries and enable atmospheric CO2 removal. The 2024 Industrial Carbon Management Strategy targets capturing and storing 250 million tonnes of CO2 annually by 2050, necessitating a robust transport network of 15,000–19,000 km of pipelines, complemented by ships, rail, and road. Ships are critical for flexible, cost-effective transport, especially for smaller or isolated emitters and regions lacking pipeline access, such as those relying on North Sea or Mediterranean storage. Europe’s 200,000 km natural gas pipeline network and the U.S.’s 8,000 km CO2 pipeline system highlight the feasibility of such infrastructure. Emerging CO2 networks, including offshore pipelines and onshore systems in countries like Belgium and the Netherlands, face high costs and long lead times. A cohesive EU regulatory framework is vital to ensure safe, equitable, and cost-optimized access to CO2 transport infrastructure, including ships, while addressing monopoly risks and cross-border coordination to support decarbonization.

Istrate2022 “Quantifying emissions in the European maritime sector (EUR 31050 EN)”, Publications Office of the European Union

Shipping is a large and growing source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as well as of local pollutants such as SO2, NOx, and particulate matter. Scientific-based evidences indicate the need for global action and policies to tackle these emissions. The EU is following an environmental strategy to reduce emissions from the shipping sector. Actions on energy efficiency, emission abatement systems and more efficient ship hulls are important in mitigating shipping emissions increase, but further actions are needed when pursuing a long-term downward trend. The most important additional decarbonisation action is the use of alternative clean fuels. When understanding the potential environmental impacts of maritime systems fuel emissions, a full life cycle perspective should be followed in order to avoid potential pitfalls. In this respect, this report performs two analysis: 1) An analysis of the GHG emitted by ships transiting in EU ports in 2019, based on the publicly available MRV-THETIS database; 2) A meta-study of the life cycle assessments (LCA) on maritime systems and alternative fuels for maritime propulsion available in the literature. The trends and gaps discussed throughout this report can serve the EU decarbonisation goals by providing recommendations for future actions aimed at quantifying and reducing maritime emissions.

Faber2020 “Fourth IMO GHG Study 2020”, International Maritime Organization

The Fourth IMO Greenhouse Gas Study 2020 reports a 9.6% increase in total shipping greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, including CO2, methane, and nitrous oxide (expressed in CO2e), from 977 million tonnes in 2012 to 1,076 million tonnes in 2018. CO2 emissions alone rose 9.3% to 1,056 million tonnes, with shipping’s share in global anthropogenic emissions increasing from 2.76% to 2.89%. International shipping CO2 emissions grew 5.6% (voyage-based) or 8.4% (vessel-based) over the same period, maintaining a stable ~2% of global CO2 emissions. Carbon intensity improved by 21–29% voyage-based and 22–32% vessel-based from 2008 to 2018, though the pace of reduction slowed post-2015. Emissions are projected to rise to 90–130% of 2008 levels by 2050, influenced by economic and energy scenarios. COVID-19 may slightly lower near-term emissions, but long-term projections remain uncertain, aligning with global decarbonization challenges.

Boyland2022 “NoGAPS: Nordic Green Ammonia Powered Ships: Phase 2: Commercialising Early Ammonia-Powered Vessels”, Nordic Innovation

The Nordic Green Ammonia Powered Ships (NoGAPS) project brought together key players from the Nordic shipping and energy value chains to develop a first-of-a-kind ammonia-powered gas carrier, the M/S NoGAPS. Their report summarises the main outputs and findings from their project, including an overview of the design decisions, general vessel arrangement, financing strategies to commercialise the first ships in the market, and how they connect to wider economic viability questions.