Scaling CO₂ economies via ports

Fragmented CO₂ transport infrastructure promotes siloed thinking and duplicate assets across Europe, just like the LNG industry wasted billions until it found out that hubs are the way out.

Emitters need accessible, cost-effective transport if carbon capture is ever going to move the needle on industrial emissions. Current options are fragmented, which inflates costs unnecessarily. The LNG industry solved this exact problem decades ago, yet we’re ignoring many of the lessons staring us right in the face.

In the 1950s, the global LNG 1 market began shaping up as producers raced to provide energy security in the wake of World War II. 2 Everyone was building bespoke distribution infrastructure. One of the most famous is Constock International Methane, a joint venture between Continental Oil and Union Stock Yards. They built the world’s first LNG carrier ship, Methane Pioneer (1959), to ship gas from their export terminal in Louisiana to the United Kingdom (Stopford2008, p. 484). However, it took many years before LNG became affordable because the race, among other things, led to duplicate infrastructure and stranded assets. 3 Only when cargo volumes were pooled through shared hubs 4 did LNG become affordable by creating economies of scale 5 so per-tonne transport costs fell by an order of magnitude 6 or more.

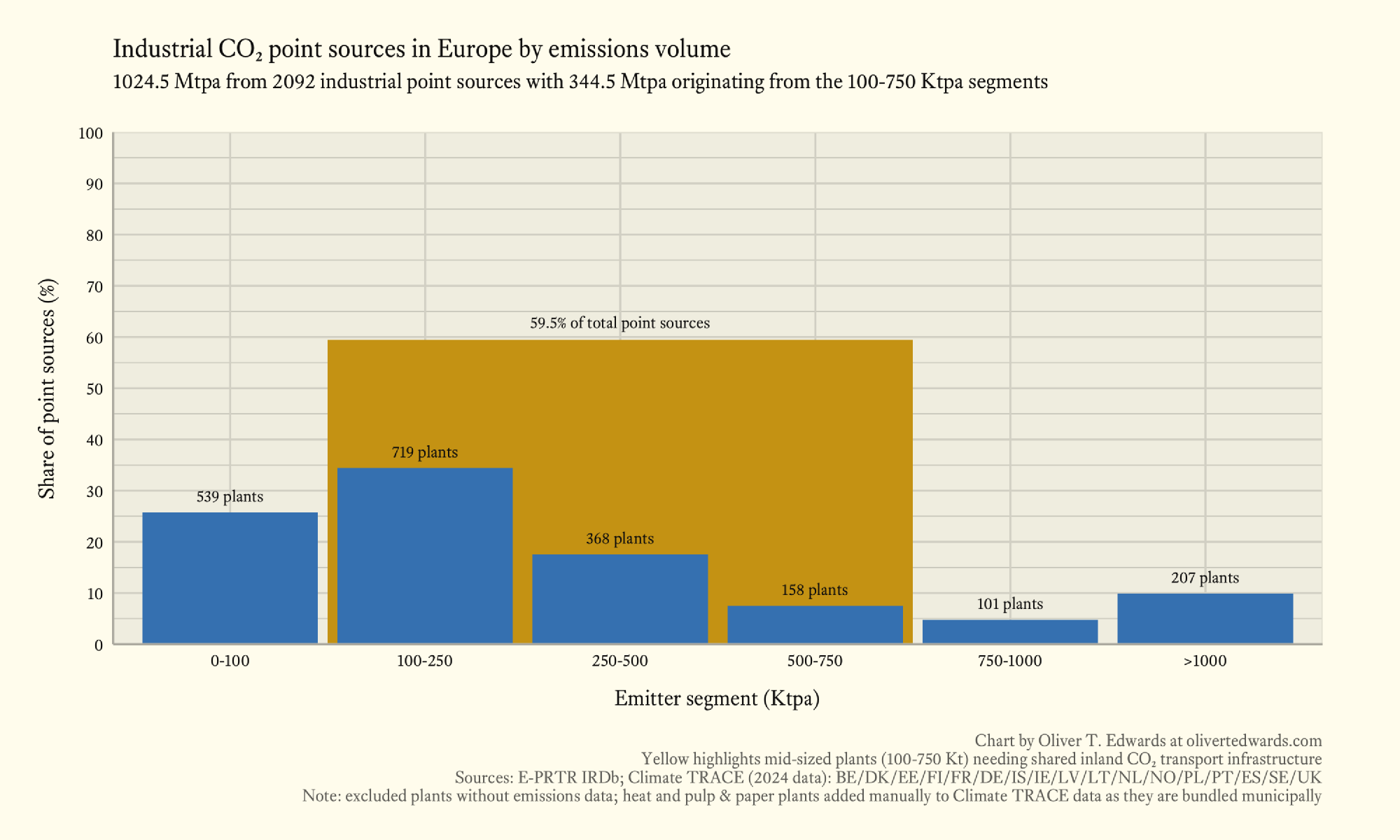

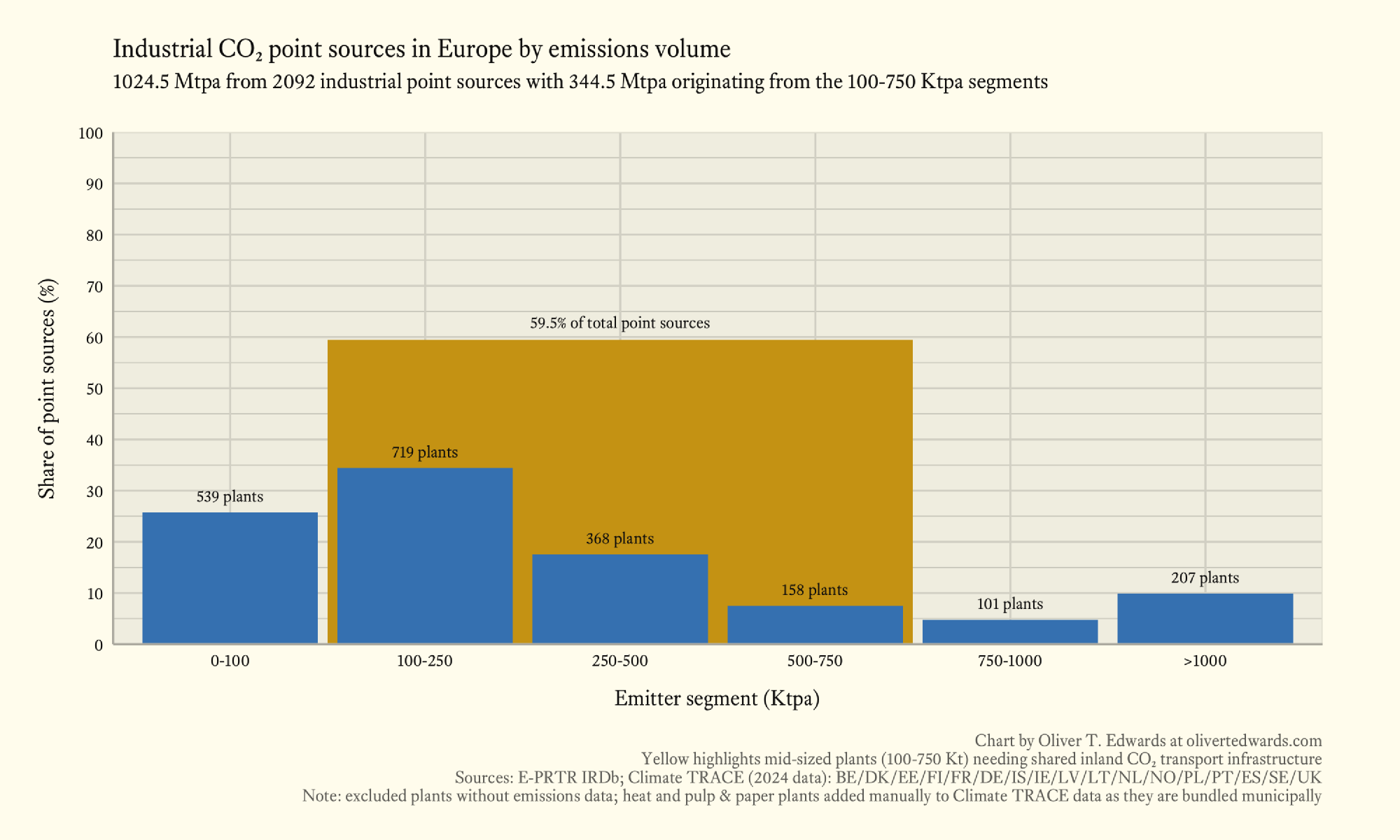

Nearly seventy years later, the CCS 7 market is repeating many of those early mistakes. Roughly 60% of industrial CO₂ point sources in Europe are mid-sized (100-750 ktpa), 8 representing a third of regional emissions. 9 Despite their huge market share, most face fragmented transport and storage options while pushing others toward designing their own terminals and ships. I’ve reviewed a number of these proposals and many look sound on paper until you think about how their strategies for interfacing with the remaining value chain actually compound issue including scale inefficiencies, just like the LNG market during the 50s.

Port-based multi-user hubs are a proven antidote. Yes, I’ll admit I haven’t built a CO₂ terminal yet, (very few have). But at Normod Carbon, where I’ve been securing terminal deals and aggregating volumes across Northern Europe, I’ve seen these patterns play out firsthand—and there’s clearly a lot to learn from LNG.

Bespoke challenges

Current CO₂ transport and storage providers have constraints that make CCS inaccessible for roughly 60% 10 of emitters.

Flagship CO₂ transport and storage solutions, like Northern Lights, 11 prioritise high-volume, high-purity streams to de-risk early operations and achieve scale. This approach makes sense for early projects, but it still leaves most of Europe’s small and mid-sized industrial point sources that dominate by number, struggling to connect affordably without shared aggregation points. I’ve spoken to many of them and know their headaches. Some of them aim to build their own quays to enable collection via ship, but adding your own vessels is both impractical and uneconomical while compounding risk across the entire value chain.

Many ports are already congested, so there’s a need for larger ships that can batch transport bundled volumes to alleviate quay-side bottlenecks. Small- and mid-sized emitters generally can’t afford bigger, more expensive ships. But, is also adds unnecessary risk to their already specialised operations in running a specific plant. Meanwhile, the number of North Sea storage wells opting for ship-based injection is increasing. Like ports, FSIU vessels have limited loading/unloading capacity. Smaller vessels will lead to congestions like those at quays, so bigger carrier vessels are still needed in this case.

There aren’t many deep-sea ports, so smaller hubs and individual emitter loading quays do make sense, but instead of shipping directly to storage, these will need transhipment and bundling onto large ships. Building intermittent storage facilities and tanks at ports is very expensive. Just like LNG, gaining economy of scale on a regional level by bundling emitters avoids wasting capital on these expenses.

Shared inland transport networks are also needed to make CCS feasibile, especially for mid-sized emitters by pooling resources to connect with regional CO₂ distribution hubs and terminals. Many share concerns over access to inland CO₂ transport. There’s a lack of purpose-built CO₂ distribution networks, like the postal service or waste disposal. Emitters don’t know what’s the best option for them to get their CO₂ to where it needs to go; it’s early days in the market, so rail and trucking distribution terminals will also help.

Concern over how much inland transport costs will make up in the total transport budget is rational. Global logistics costs by transport mode are roughly 75% trucking, 15% maritime, 5% air, 5% rail (Rodrigue2024, ch. 7.4), and even as an average, it indicates fear particularly for emitters further inland. Inland distribution terminals like a postal service could help coordination and economy of scale, but must first focus on railway and trucking terminals. For small to mid-sized emitters placed inland, they can’t afford to build a pipeline themselves, so inland transport is needed, preferably at scale to reduce volume fluctuation risks, get better deals, average out capex, reduce operating expenses, and make it cheaper overall.

So, how about pipelines? Pipelines have long lead times, are not flexible, and require serious land development and zoning/regulatory kinks to be worked out, as noted in my post on land development for CO₂ hubs. Scoping a pipeline for future use is also difficult because nobody knows how much capacity is needed on the CO₂ grid in the next 20 years, let alone 50. Transitioning to green energy is desirable, but with Germany and many other countries doubling down on their LNG gas grids for energy security, LNG could be a significant part of the energy mix for many years to come. If increasing energy consumption means higher growth and welfare, then CO₂ emissions could keep growing, increasing the need for CO₂ pipeline capacity to handle more emissions. We will also need to build more green energy infrastructure, which will require more emissions up to a certain point. Careful planning is needed to plan, build, operate, and maintain a CO₂ pipeline grid for years to come, which also means increasingly postponed implementation timelines, further increasing the need for particularly railway and ship transport.

Much like LNG’s early race, building bespoke infrastructure doesn’t solve the current fragmentation issues, it risks further exclusion of not just mid-sized emitters, but also smaller and large emitters as value chain complexity compounds.

Market challenges

Europe

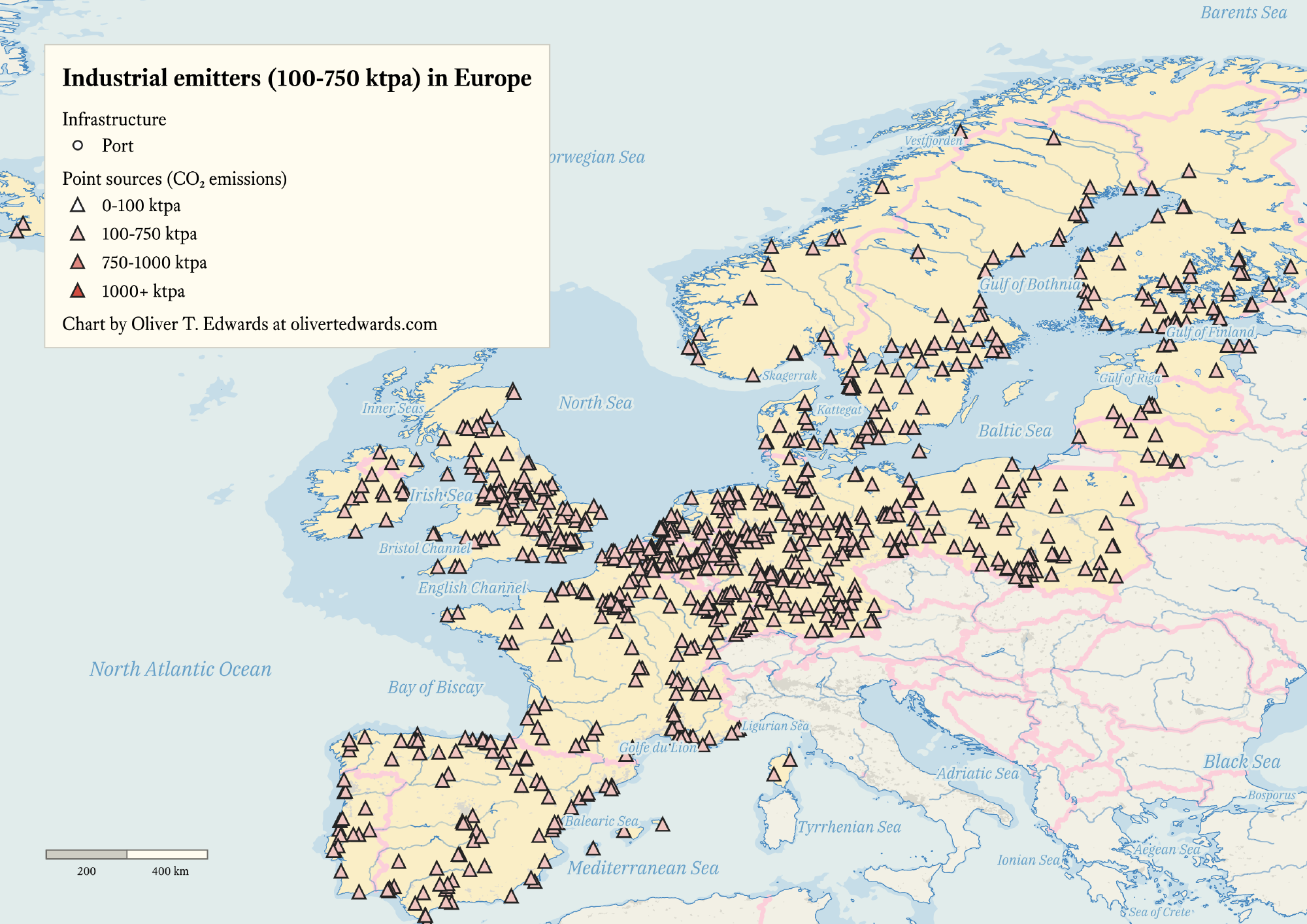

The European emitter market underscores the bespoke fragmentation outlined above, with mid-sized sources dominating but struggling with connectivity. Having assembled a dataset on point sources and their mean distances to port and railway across Europe, I’ve examined the composition segmented by small-sized (<100 ktpa), mid-sized (100–750 ktpa), large-sized (750-1000 ktpa), and massive-sized (>1000 ktpa) emitters across Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom—with special attention on the Netherlands, Poland, and Sweden for their uniquely different geographic and infrastructural differences worth examining as reference cases. This reveals that large CO₂ emitters (>750 ktpa) typically have access to greater capital, allowing independence to invest in CCS, while small (<100 ktpa) and mid-sized emitters are more dependent on shared transport infrastructure and pooling resources to share costs.

Aggregating CO₂ output from multiple small and mid-sized emitters will likely create sufficient transport demand to justify shared infrastructure, such as rail or multi-user pipelines, especially in regions with high emitter density like the Netherlands or Poland’s Śląskie region. The prevalence of small and mid-sized emitters by number of plants—particularly in Sweden (pulp and paper) and the Netherlands (chemical plants)—contrasts with Poland’s mix of large coal-based and smaller industrial emitters. Offshore sites are the most prominent storage wells at this point, so good port access is critical given that tonne-mile shipping costs are lower than any other mode (thanks to economy of scale). Onshore storage continues to meet regulatory hurdles and public opposition, increasing the importance of shipping.

On average, LNG shipping costs about €0.005-0.01 per tonne-mile and costs for CO₂ shipping are close to this figure, railway €0.05, and trucking €0.25 (ranges confirmed through dialogue with various national providers). CO₂ shipping costs must also take into account the unique cooling and pressurisation it requires, which is different from LNG, and volatility due to fuel prices (Stopford2008, p. 35), which will affect actual prices—shipping cost is probably the most volatile of all costs at this point in the market.

59.5% of industrial CO₂ point sources fall in the mid-sized segment, accounting for roughly 33% of total regional emissions (344.5 of 1024.5 mtpa).

The top CO₂ emitting sectors within the mid-sized segment in Europe are waste to energy, natural gases, and other gases. Waste to energy and cement are the sectors that most easily decarbonized, while natural gases and other gases are emissions from a variety of processes including LNG terminals, where carbon capture is less easily implemented in the regional value chain.

| Sector | Emissions (Mtpa) | Share (%) of mid-sized segment |

|---|---|---|

| Waste to energy | 63.2 | 18 |

| Natural gases and other gases | 52.4 | 15 |

| Cement | 37.5 | 10 |

| Mid-sized segment total | 344.5 |

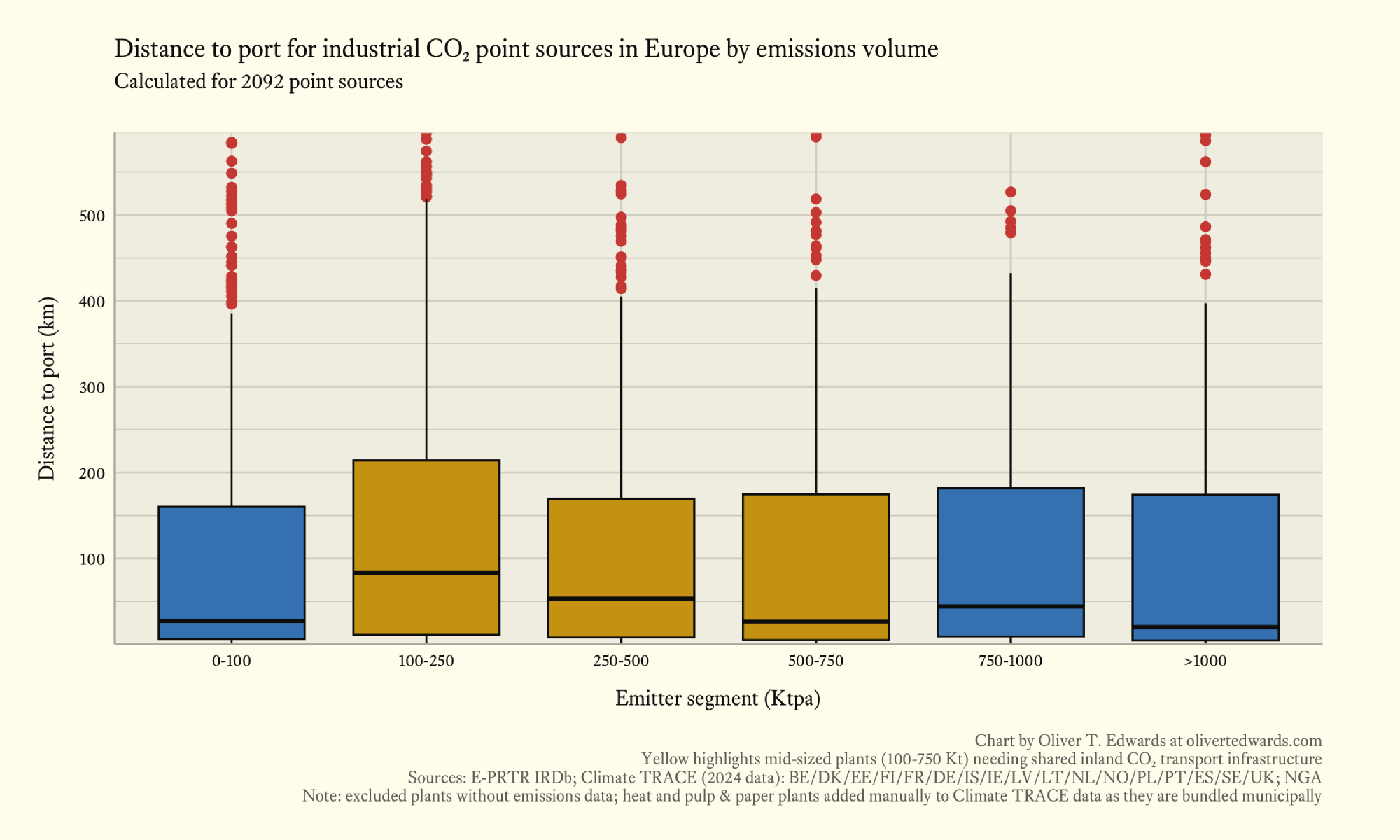

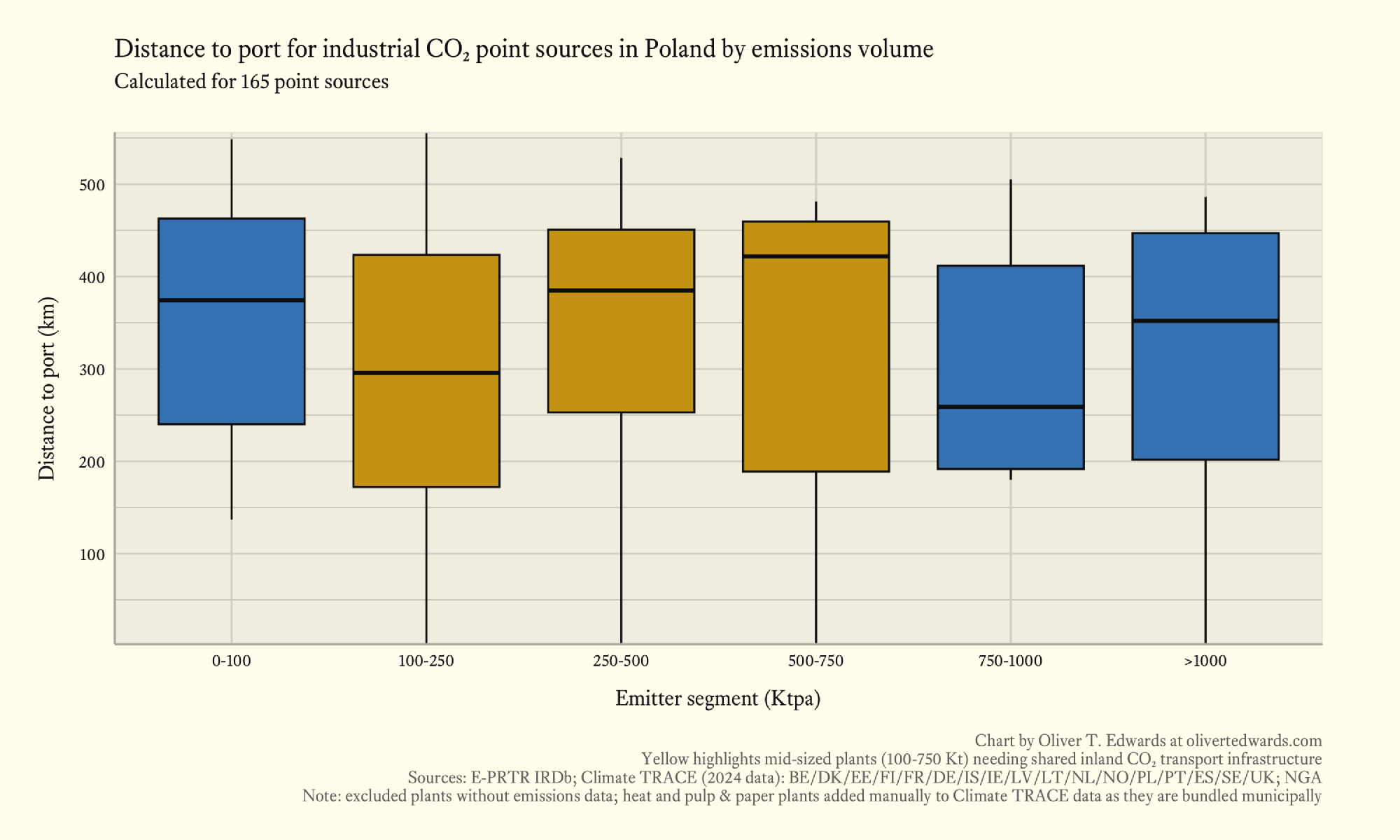

Across all segments, there is about a 200 km difference in point source distance to port from the lower quartile (ca. 1 km distance) and the upper quartile (ca. 210 km distance) due to varying geographies and coastal access across Europe. Mean distance to port of 100-250 segment is around 75 km; 250-500 segment around 50 km; 500-750 segment around 25 km. Average distances to ports vary significantly, impacting CCS feasibility; Poland’s inland location results in longer port distances (Gdańsk), while Sweden and the Netherlands benefit from shorter distances to coastal terminals. Small emitters, with limited financial resources, are disproportionately affected by long port distances, as shipping CO₂ to offshore storage (North Sea sites) requires costly transport solutions without shared infrastructure. There are also a lot of outliers that will require further tailored investments in inland transport solutions, though each nation will have to deal with this issue separately. Shared port terminals or multi-modal hubs (combining rail and shipping) can lower barriers for small emitters, especially in Poland, by connecting inland CO₂ sources to offshore storage.

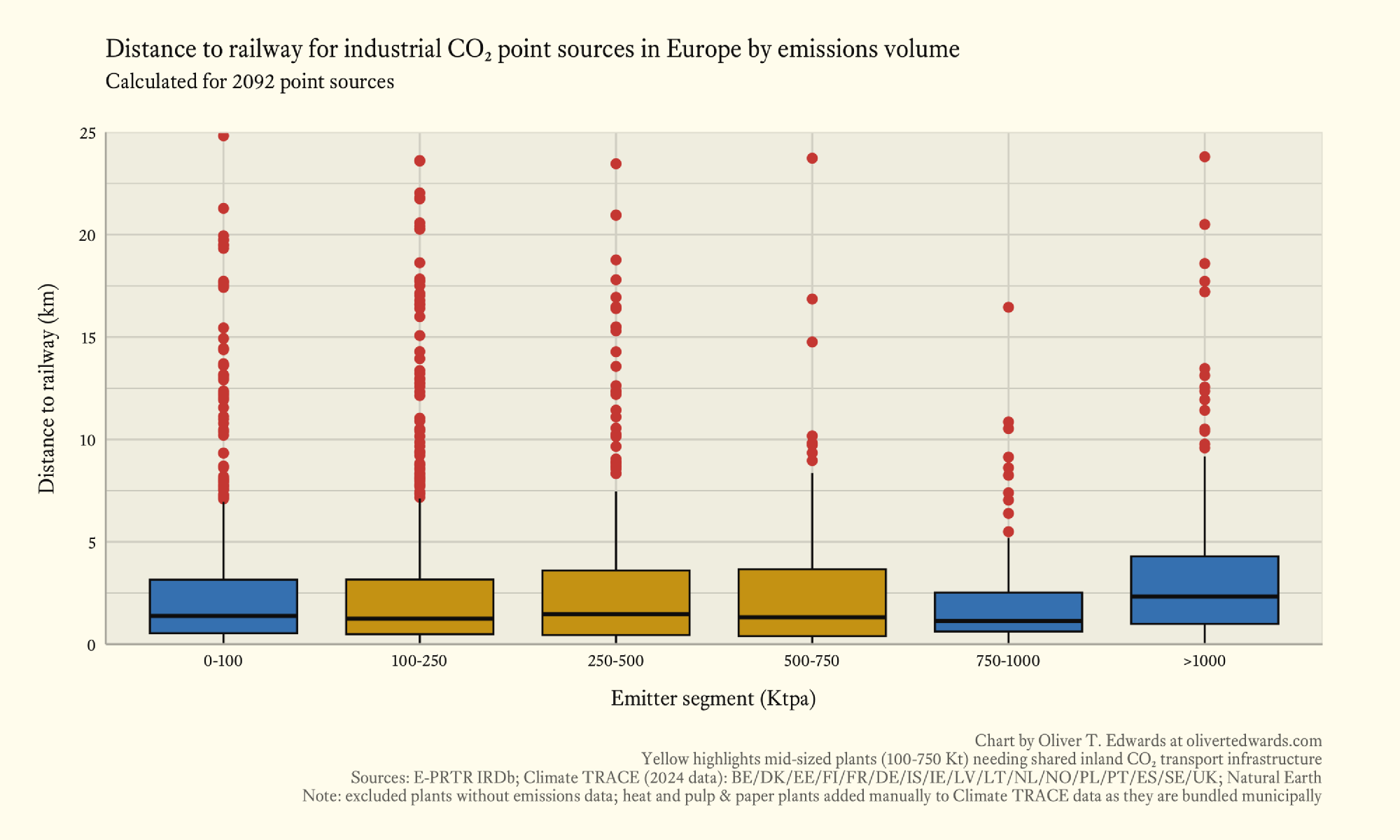

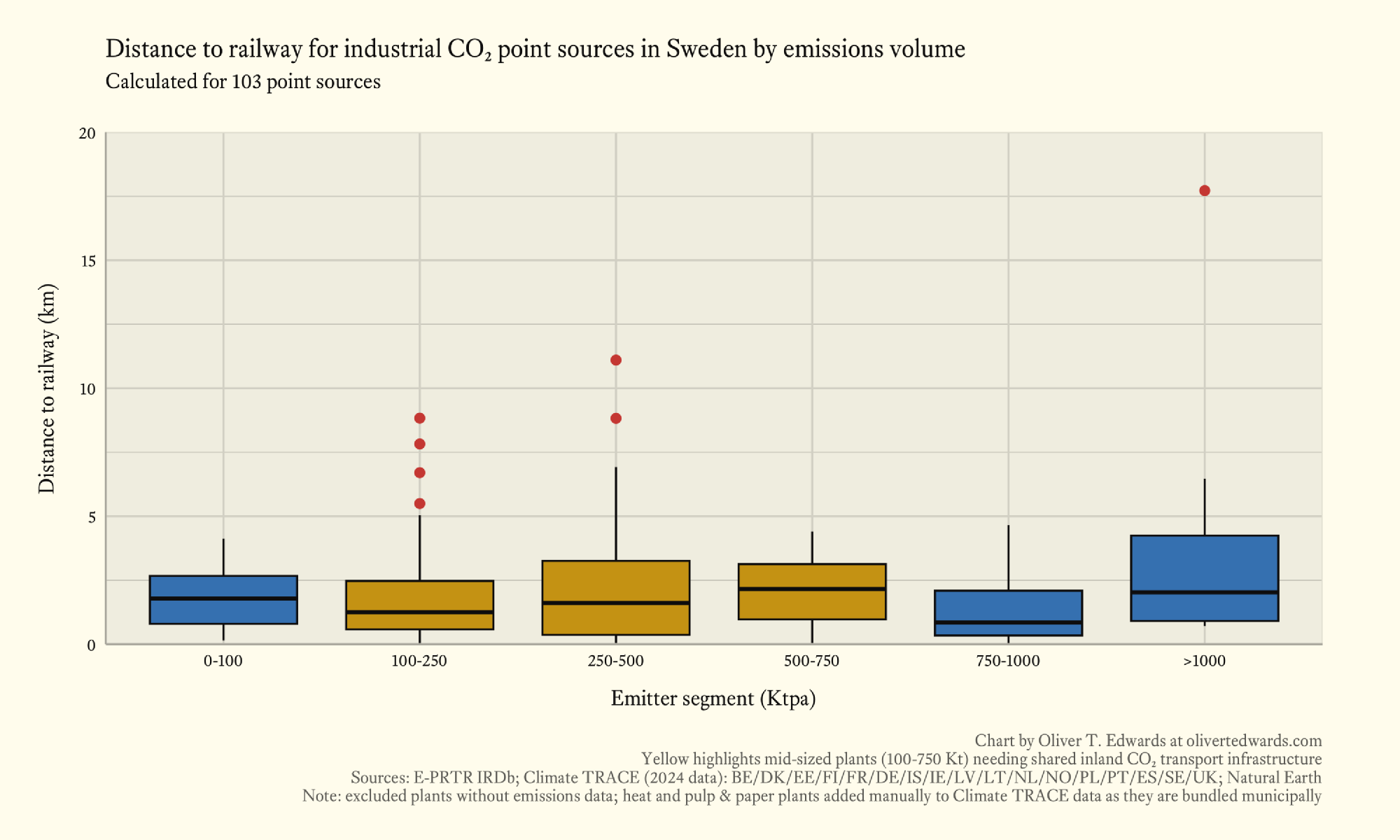

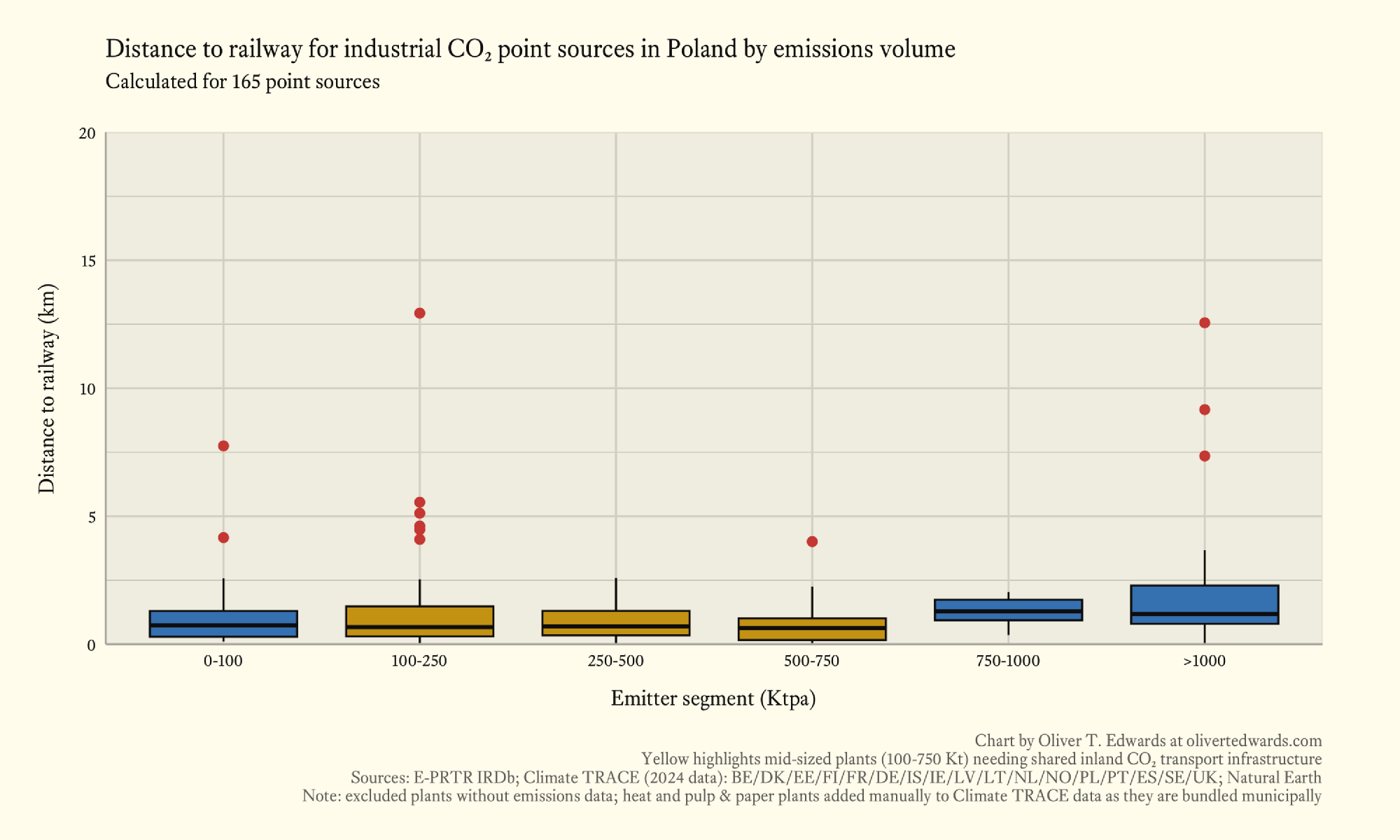

Across all segments, there is about a 3 km difference in point source distance to nearest railway from the lower quartile (ca. 1 km distance) and the upper quartile (ca. 4 km distance), and mean distances are also stable across all segments hovering in the 1-2 km distance range. The stable mean distance isn’t too surprising given the statistical significance distances computed for 2092 point sources. Rail transport is often more cost-effective than pipelines for small-to-medium CO₂ volumes over medium distances, making it a key option for inland emitters, particularly in Poland and the Netherlands with dense rail networks. Shorter average distances to rail infrastructure (compared to ports) in Poland and the Netherlands support the feasibility of rail-based CO₂ transport, especially for small emitters pooling resources. Developing shared rail terminals or CO₂ collection hubs can lower transport costs for small emitters, enabling access to CCS networks, especially in Poland where rail is critical due to long port distances. Short distance to railway is important for emitters without direct port access.

The data provides a sense of scale of the fragmentation issues, showing the need for shared solutions like hubs to bridge inland gaps to offshore storage.

Sweden

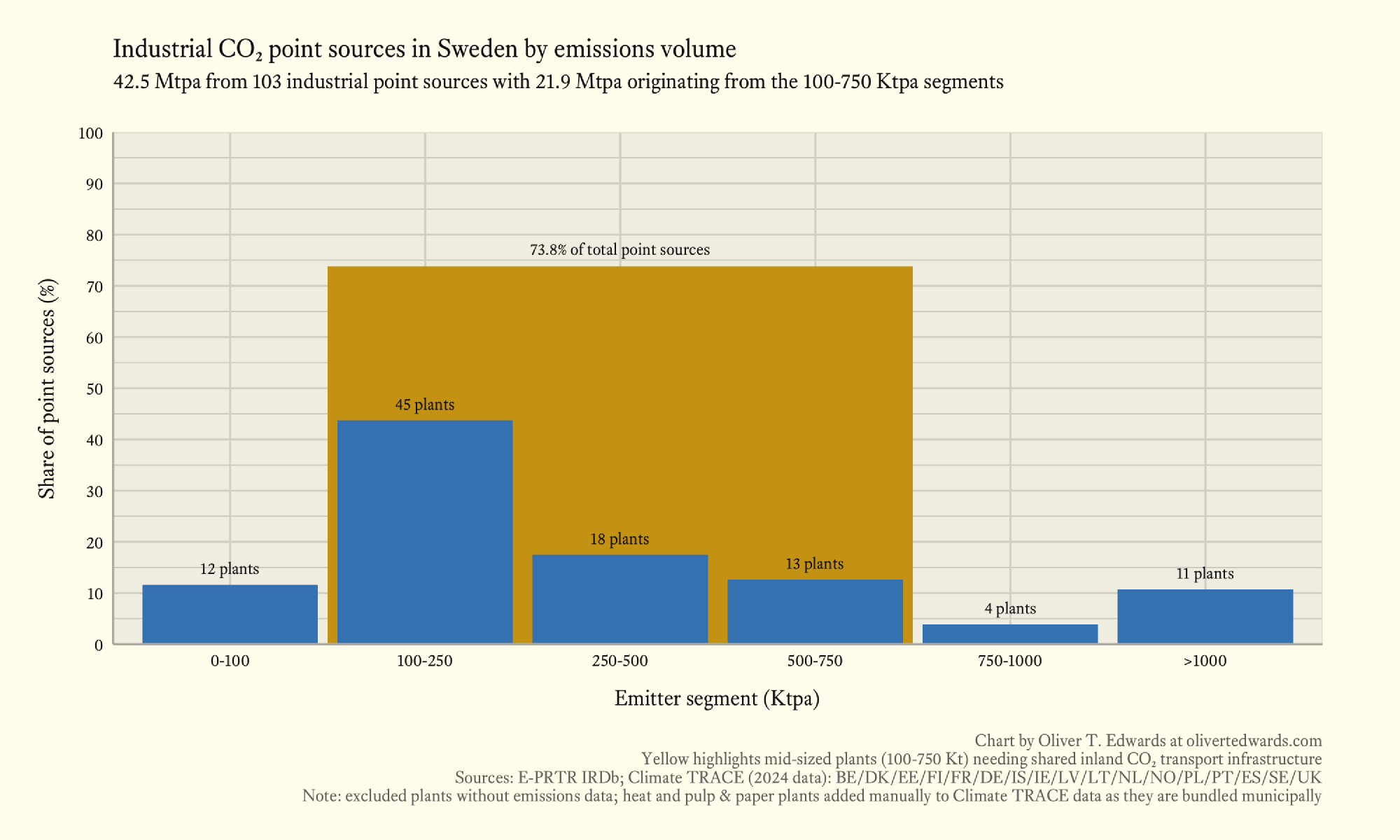

In Sweden, an evenly distributed network of hubs is key because emitters are spread across 1,500 km from north to south. Railways are particularly important in the southern hinterland where emitters are further inland. That also means southern hubs might need larger amounts of buffer storage to account for greater seasonal variations when pooling cargo volumes. Building shared hubs and transport networks is especially important in Sweden given the overwhelmingly large market share of mid-sized emitters. This is the approach we’re taking at Normod Carbon to connect emitters efficiently.

73.8% of industrial CO₂ point sources fall in this segment, accounting for 51% of total national emissions.

The top three CO₂ emitting sectors within the mid-sized segment are pulp and paper, biomass and bioenergy, waste to energy. All of these sectors are rated as easily decarbonised sectors, making it technologically easier to decarbonise Swedish industry than many other European countries. This should moderately ease the cost burden of implementing carbon capture for many companies.

| Sector | Emissions (Mtpa) | Share (%) of mid-sized segment |

|---|---|---|

| Pulp and paper | 9.2 | 42 |

| Biomass and bioenergy | 6.8 | 31 |

| Waste to energy | 3.7 | 16 |

| Mid-sized segment total | 21.9 |

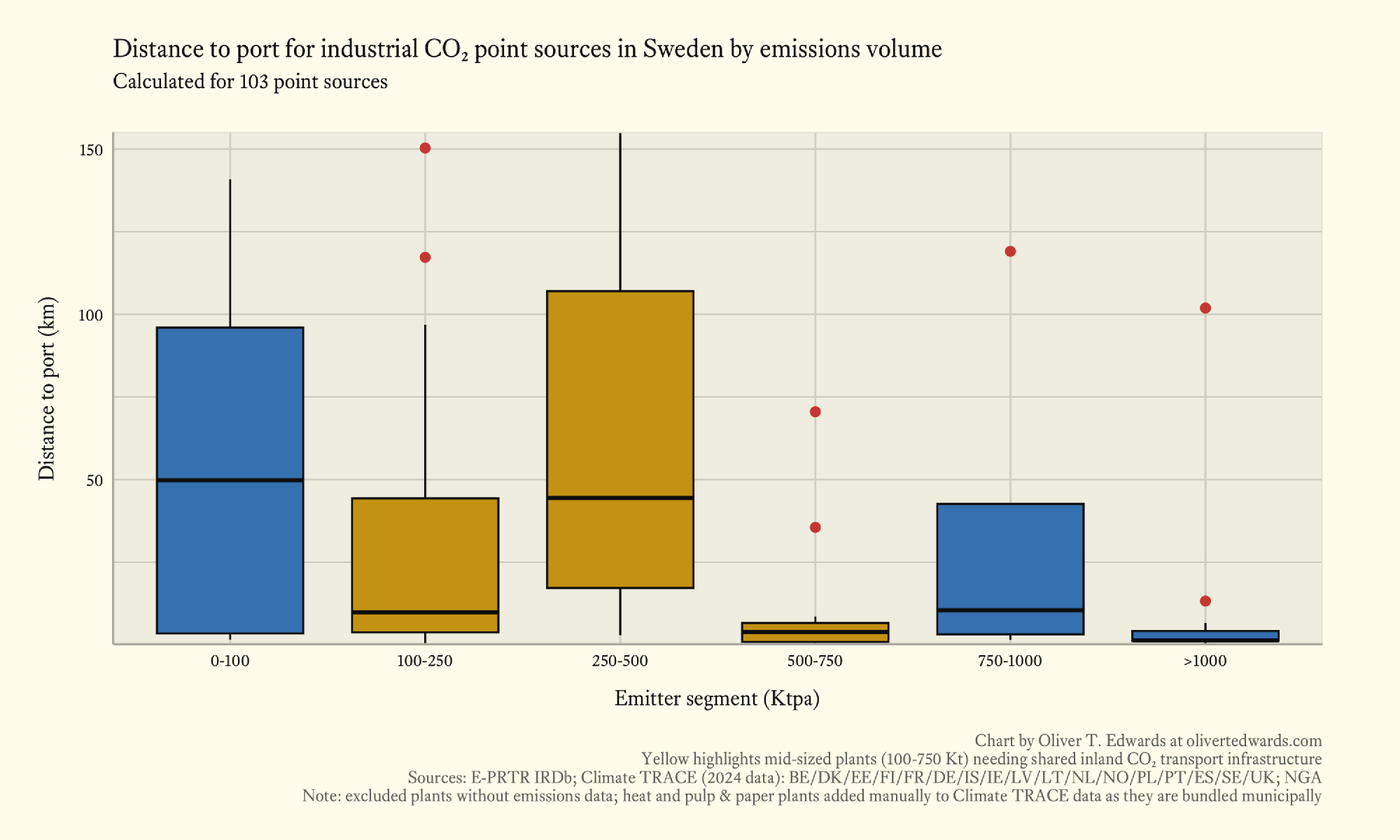

Across the mid-sized segment, mean distances from point source to nearest port range from 5-48 km, and a 104 km difference between the lower quartile (1 km) and the upper quartile (105 km) distances. In general, emitters within the northern regions are located within close proximity to ports. The main issue for providing port accessibility is in the southern regions, though many emitters are within relatively close proximity to railways. Further inland towards Norway, there are a few outliers with exceptionally long distances to ports. However, most of the railway routes passing these are generally already outfitted for heavy industrial use, which is positive for dealing with outliers in the market.

Across all segments, there is about a 3.5 km difference in point source distance to nearest railway from the lower quartile (ca. 0.5 km distance) and the upper quartile (ca. 4 km distance), and mean distances are also stable across all segments hovering in the 2 km mark. The short distances across the market aren’t too surprising as the nation relies heavily on the railway network to move goods across regions as well as passengers. The key thing is to build out well-placed CO₂ terminals at ports connecting to this railway network, while potentially taking advantage of onshore cave systems to reduce the cost of building out intermittent CO₂ tanks before shipping volumes off to the North Sea for permanent storage.

Poland

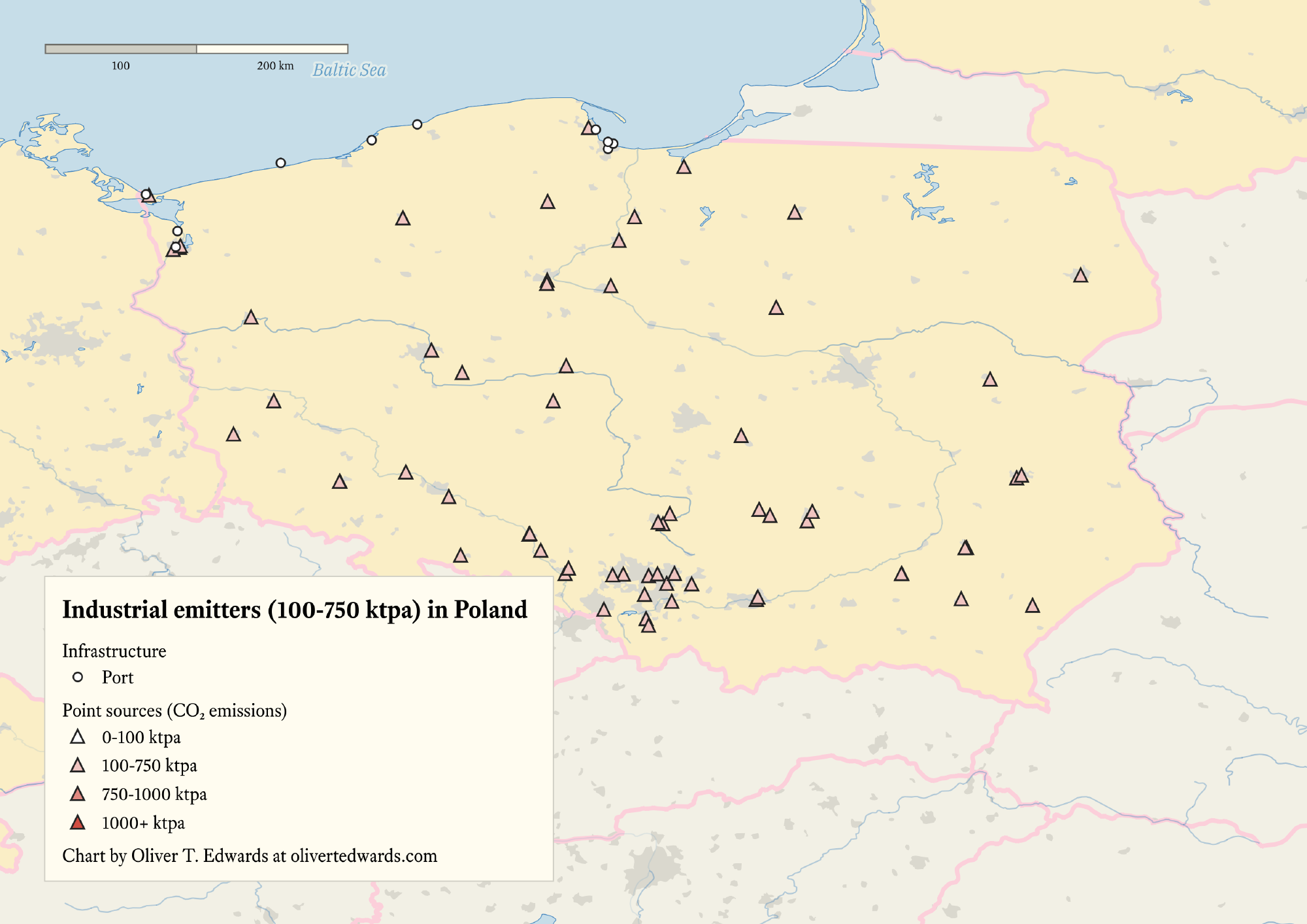

In Poland, the short coastline of 550 km means there are few major ports. The country also stretches 650 km inland, and with many mid-sized plants scattered across the country with some clustering around Katowice, railways are essential to make ports accessible. There are plans to develop extensive onshore CO₂ storage and pipeline networks (Rossi2023), but these will take time to build out. So, long distances amplify the consequences of bespoke infrastructure, but dense rail networks position hubs as bridges to offshore storage, enabling coordination across segments.

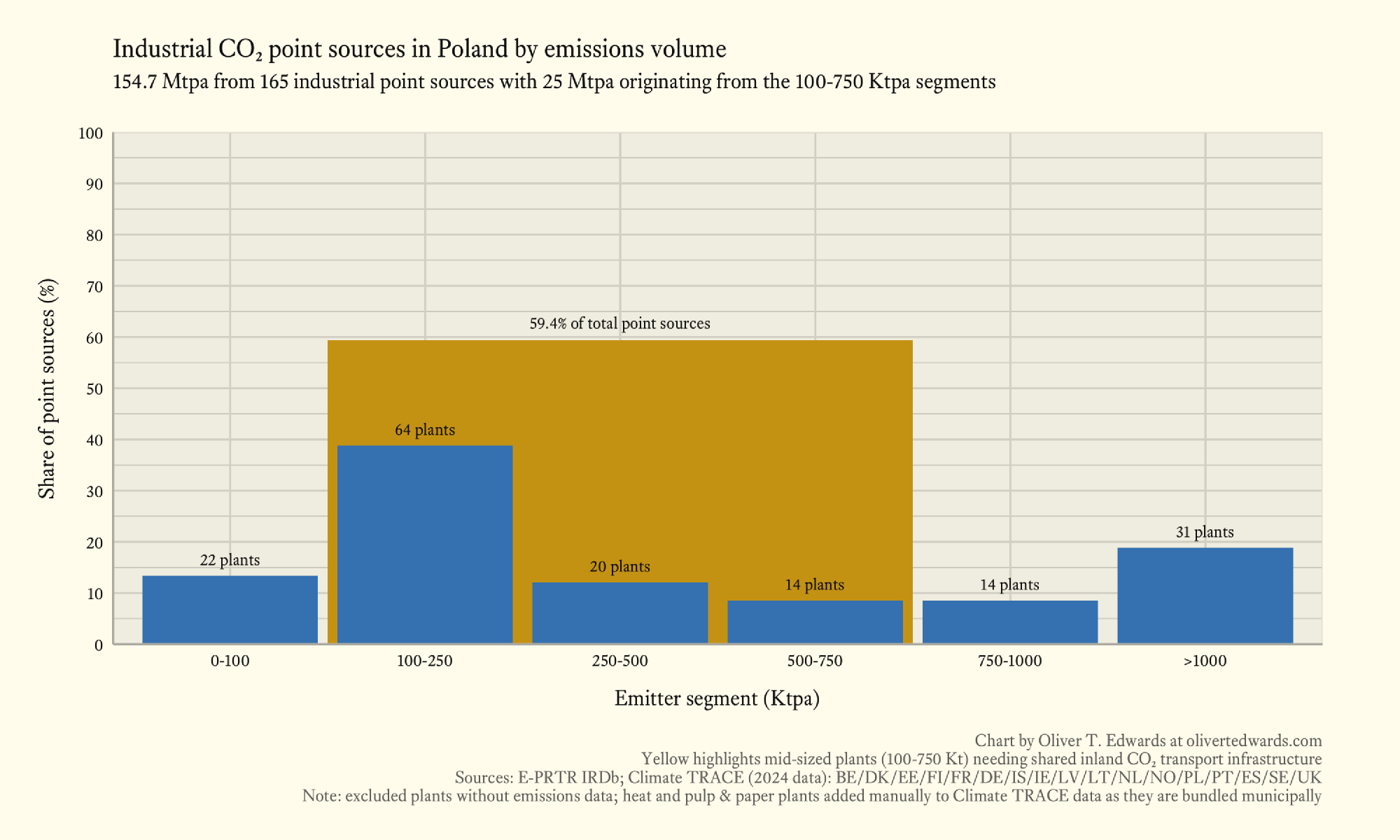

59.4% of industrial CO₂ point sources fall in the mid-sized segment, accounting for roughly 16% of total regional emissions (25 Mtpa of 154.7 Mtpa). The market is also dominated by large emitters (>1000 ktpa) in coal and steel sectors, but smaller industrial facilities could benefit from coordinated transport to reduce costs, especially given limited port proximity (Rossi2023). Onshore storage is in development, although if we are to use the rest of the European market as a guideline, this will also take longer than expected, increasing the relevance of port access in the short and medium term.

The top three CO₂ emitting sectors within the mid-sized segment in Poland are coal and lignite, other, and cement. Coal and lignite, and cement are the easiest industries to decarbonise. The other category consists of many plants that are much more difficult to decarbonise through carbon capture. However, since coal and lignite makes up 38% of the mid-sized segment, not to mention that most of the massive-sized emitters are also from this sector, the country should be relatively straightforward to decarbonise from a technological perspective. I’m planning a separate analysis on decarbonising countries with an overwhelming amount of massive-sized emitters such as Poland.

| Sector | Emissions (Mtpa) | Share (%) of mid-sized segment |

|---|---|---|

| Coal and lignite | 9.6 | 38 |

| Other | 2.5 | 10 |

| Cement | 2.2 | 8 |

| Mid-sized segment total | 25 |

Across the mid-sized segment, there is about a 270 km difference in point source distance to nearest port from the lower quartile (ca. 180 km distance) and the upper quartile (ca. 450 km distance), and mean distances varying between 300, 380, and 460 km. Nearly all emitters have a large distance to port that is in a range manageable with railway transport, although trucking will be an issue, also in terms of load port onto the road network. Poland is also working on onshore storage to alleviate this challenge, but this might not pan out, since we have not seen any good examples in the EU of this happening just yet—perhaps in the future. Pipelines would make a lot of sense, although lead times and modelling of future demand scenarios present a big challenge for implementation. Mean distance to port of 100-250 segment is 300 km; 250-500 segment 380 km; 500-750 segment 420 km. Mean distance to port for emitters in large-sized segment (750-1000) is lower than all other segments at 250 km, while higher for massive-sized emitters, so coordination across the whole market is essential, especially for mid-sized emitters.

Very short distances to railway (around 1 km for the mid-sized segment and 2 km for the 750-1000 and >1000 ktpa segments). Industrial regions can also make rail a viable option for pooling CO₂ from small and mid-sized emitters to reach ports or storage hubs, while pipeline and onshore storage networks develop.

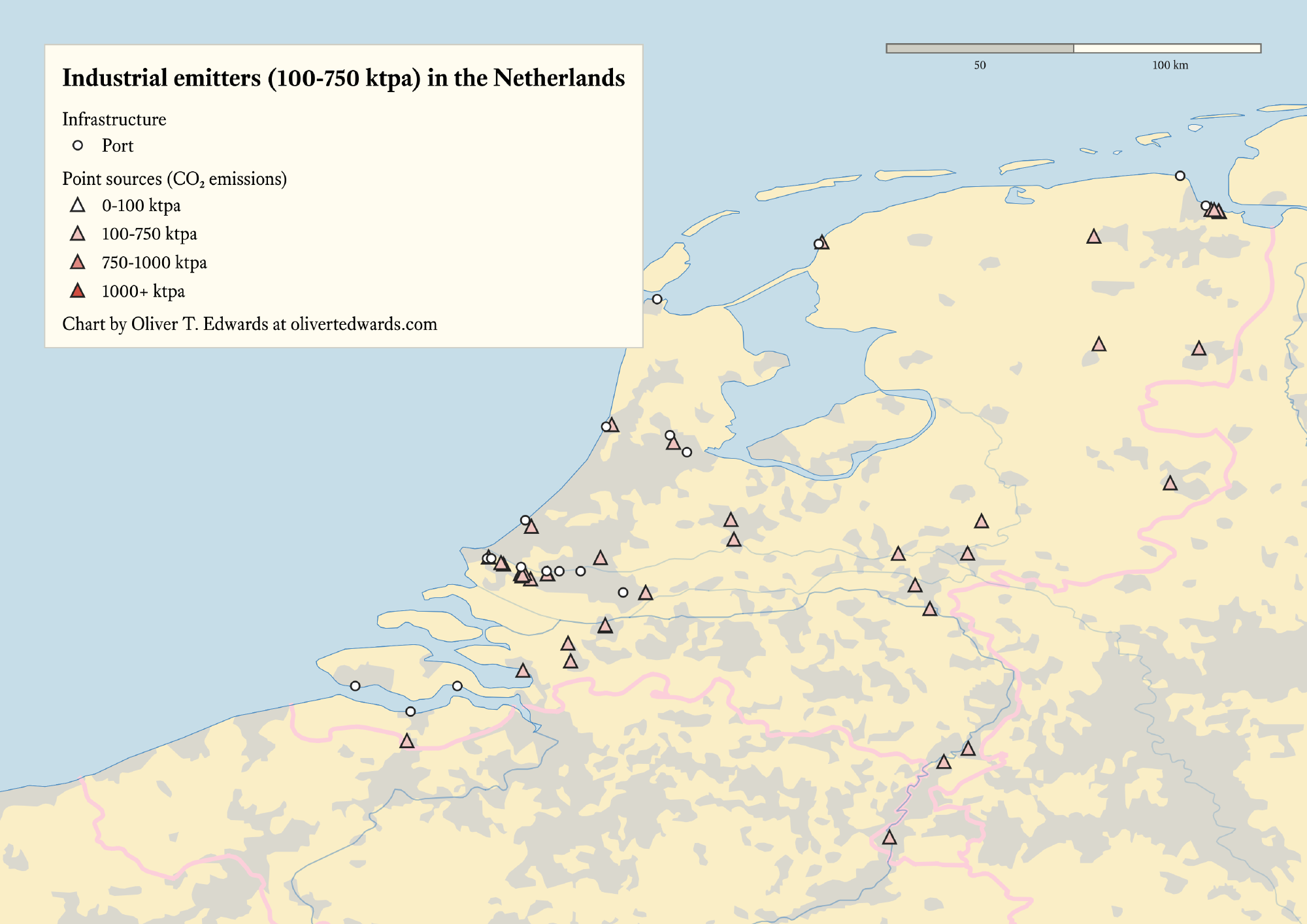

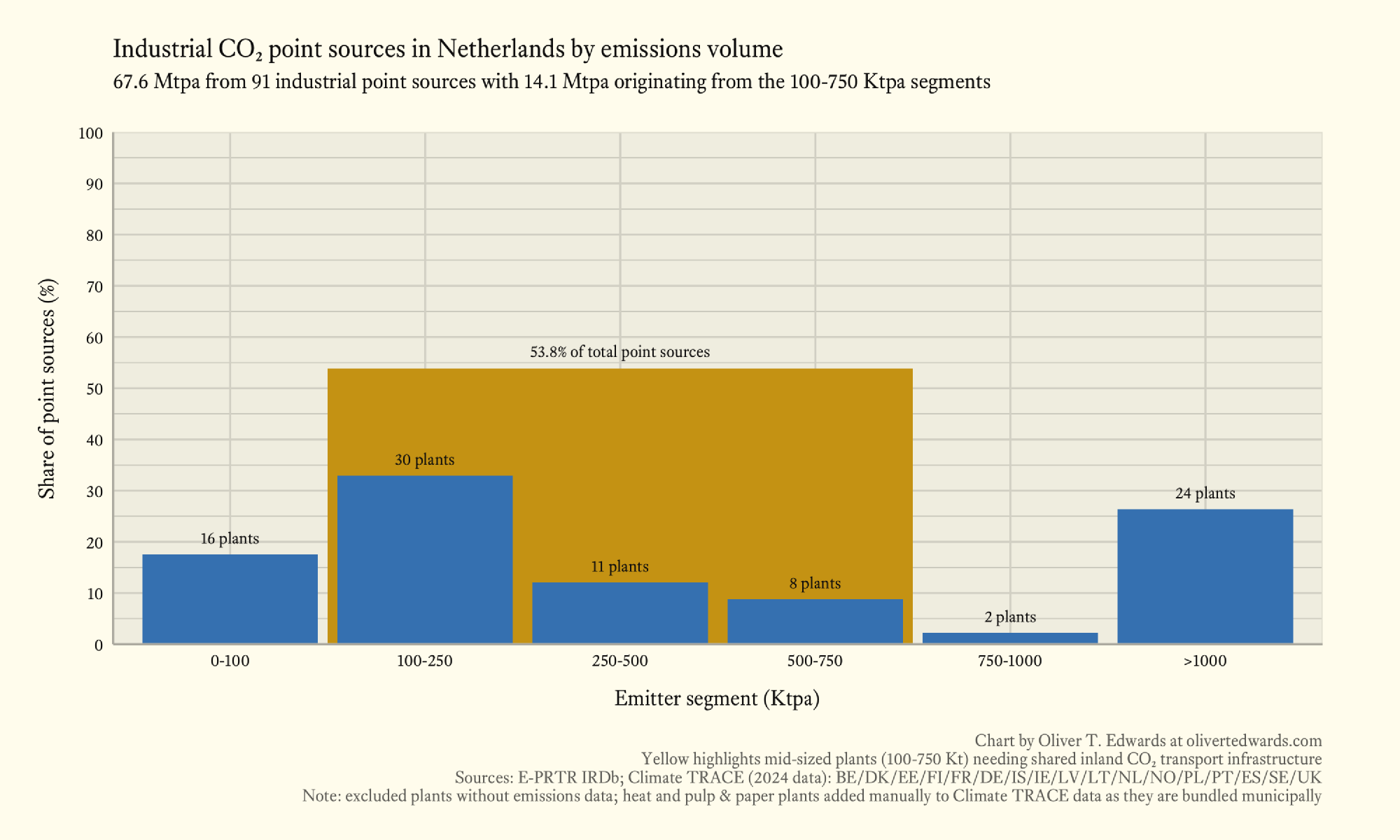

Netherlands

The Netherlands offers a prototype for hub potential, with heavy clustering around ports enabling easy aggregation but demanding coordination to avoid bespoke silos. In the Netherlands, delta clustering positions ports as natural hubs, but without coordination, mid-sized emitters risk bespoke isolation—Porthos shows how bundling unlocks scale for the value chain.

53.8% of industrial CO₂ point sources fall in the mid-sized segment, accounting for roughly 20% of total regional emissions (14.1 Mtpa of 67.6 Mtpa). A balanced mix of mid-sized and massive-sized emitters could make it easier for smaller emitters to bundle up with larger ones in general. Heavy clustering around ports, especially around the Rhine and Meuse deltas which connect with Germany, are great opportunities to connect with the entire industrial value chain—no wonder the Porthos project is a good placement.

The top CO₂ emitting sectors within the mid-sized segment in the Netherlands are natural gases and other gases, waste to energy, refinery. Waste to energy and refining are the sectors that most easily decarbonised, while natural gases and other gases are emissions from a variety of processes including LNG terminals, where carbon capture is less easily implemented in the regional value chain. There are a lot of other industries connected with the Rhine, and the amount of ships around the Delta make it a good location for receiving CO₂ captured onboard merchant vessels with onboard carbon capture systems (OCCS).

| Sector | Emissions (Mtpa) | Share (%) of mid-sized segment |

|---|---|---|

| Natural gases and other gases | 3.8 | 26 |

| Waste to energy | 3.5 | 24 |

| Refinery | 0.8 | 5 |

| Mid-sized segment total | 14.1 |

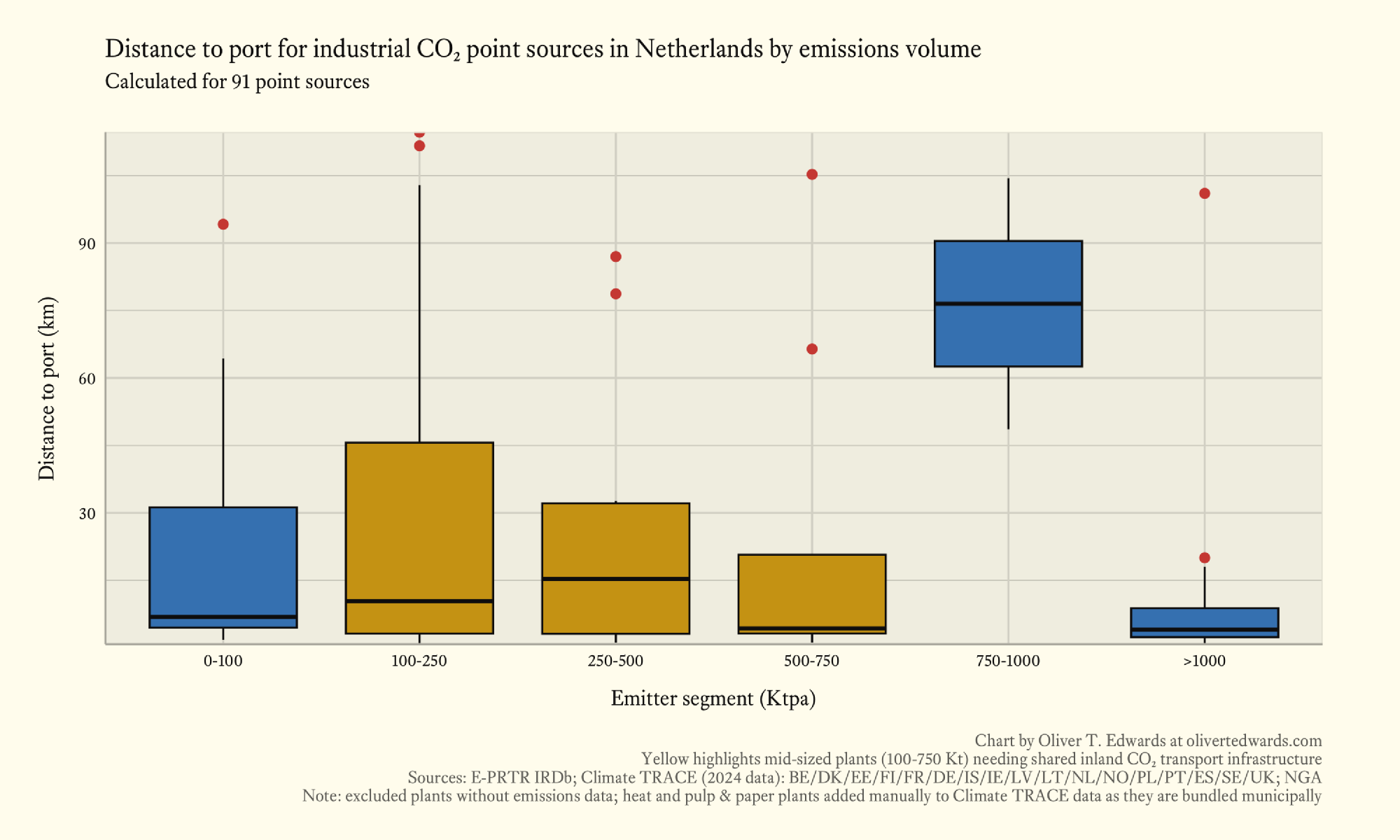

Across the mid-sized segment, there is about a 43 km difference in point source distance to nearest port from the lower quartile (ca. 2 km distance) and the upper quartile (ca. 45 km distance), and mean distances are around the 10-15 km range. Massive-sized emitters are very close to ports, making transport logistics easier for the nation in general, but demanding more coordination among smaller and mid-sized emitters, as they might not be able to bundle up easily with massive-sized emitters building out their transport networks. Mean distance to port of 100-250 segment is 10 km; 250-500 segment 15 km; 500-750 segment 4 km. Mean distance to port for emitters in large-sized segment (750-1000) is unusually large at 75 km, making an analysis of planned pipeline and railway routes all the more relevant as they will likely pass near mid-sized emitters.

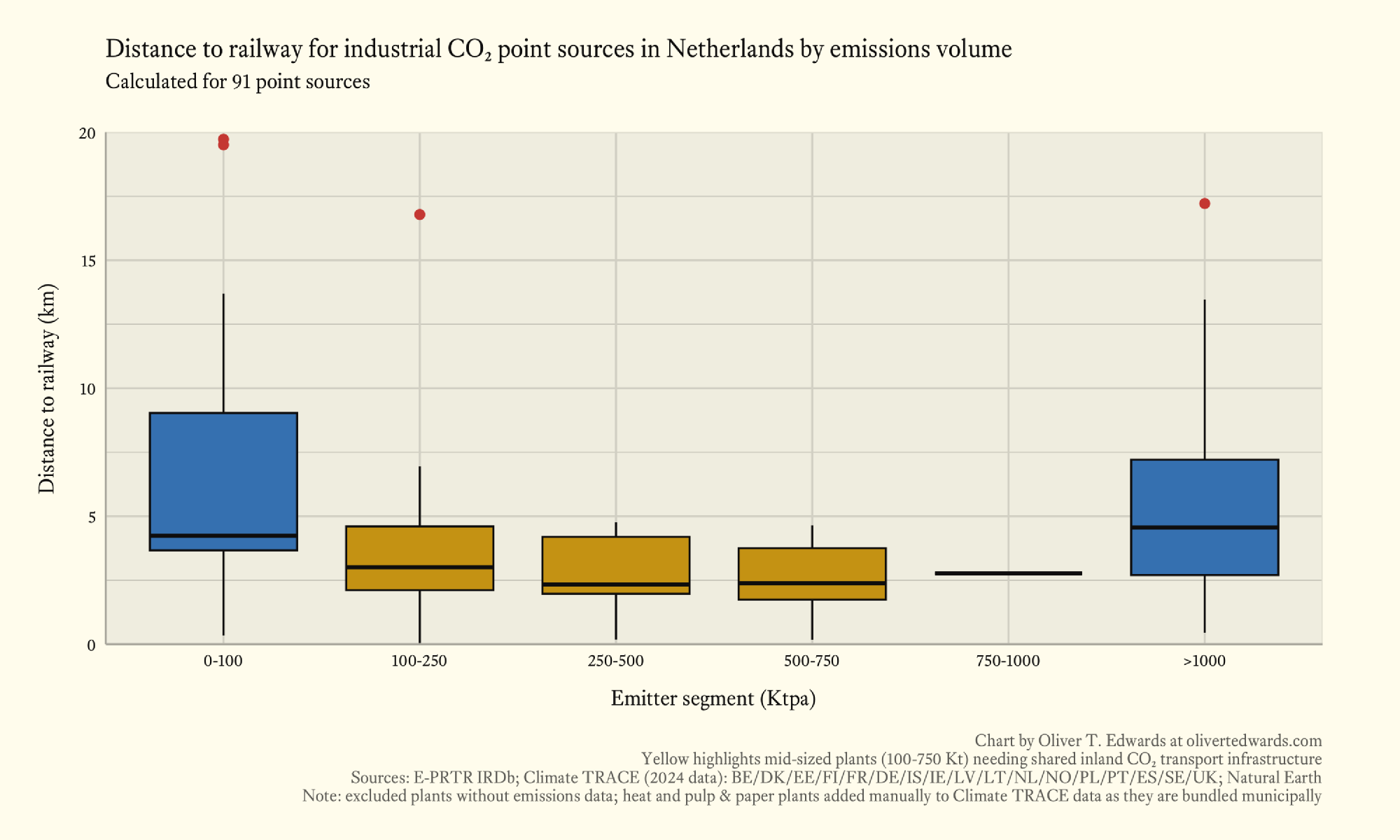

Across the mid-sized segment, there is about a 2 km difference in point source distance to nearest railway from the lower quartile (ca. 2 km distance) and the upper quartile (ca. 4 km distance), and mean distances are also stable across all segments hovering around the 2.5 km distance range. Short mean rail distances for the mid-sized segment due to the geography and dense rail networks enable small emitters to access shared rail transport, complementing inland waterway options for CCS, especially Rotterdam with its industries concentrated around the Rhine and Meuse deltas.

Another interest details is the law on worst case scenario risk benchmarks from the mining industry increases the geological storage costs significantly (Jan Berre), much like the Basel IV, because the law affects the risk premiums and thereby the interest rates on funding for these projects. It’s not strictly a shared infrastructure challenges, but an interesting example of how laws can also affect costs negatively. The most frustrating things about Basel IV is that it disconnects risk scores from the actual physical risks which are much lower than the attempt at standardising risk can accommodate.

Scaling via ports

Innovations do not create change. That is rare. Innovations succeed by exploiting change, not attempting to force it.

Peter Drucker

Ports acting as multi-user hubs solve most of the big issues with carbon management at once. They can aggregate volumes, smooth seasonal swings, spread capital requirements, and create more resilient value chains for emitters, railways, shipowners, storage operators, and so on.

Nearly all proven storage capacity is clustered around the North Sea and onshore storage continues to face public resistance almost everywhere. So, for the time being, every emitter (coastal or inland, large or small) needs reliable, affordable access to a port to handle their CO₂ volumes.

Long distances and modest individual volumes make bundling essential. Storage operators demand minimum cargo sizes and stable delivery schedules. Seasonal variations (especially bioenergy and waste-to-energy low seasons) create volume swings that create serious economic risk in the value chain without the right amount of hub storage buffering.

Principles

Aggregating volumes lowers costs by collecting CO₂ from many emitters and routing it to shared compression, intermittent storage, and loading jetties. This unlocks economies of scale that individual projects can’t achieve on their own. Shared infrastructure avoids the capex duplication we saw in early LNG, where bespoke builds stranded billions.

Logistics become reliable by directly connecting all transport modes from inland capture to offshore storage. Shared hubs act as critical transfer points, just like distribution centres in the postal system. This reduces the coordination headaches emitters face today, where fragmented networks leave mid-sized players guessing how to move their CO₂.

Early projects are de-risked by sharing permitting, safety regimes, monitoring, and modular capex across dozens of customers and offtake services. Instead of each emitter navigating regulations alone, hubs spread the load and accelerate timelines. We’ve seen this work in LNG hubs, cutting per-unit risks by 20-40%.

Maritime decarbonisation is enabled in parallel because hubs create a natural offloading point for ships with onboard carbon capture and storage (OCCS) systems. This strengthens the overall carbon market without requiring separate infrastructure.

Large hubs lay the foundation for the CO₂ economy by supporting utilisation facilities to a much greater degree. This realises the shift from pure storage to production of green fuels and chemicals. Multiple ports spread risk, balance volumes across seasons and regions, and prevent single-point congestion failures. These are the elements that turned LNG from an expensive novelty into a global commodity, and they are just as realistic a path for CO₂.

Especially mid-sized industrial emitters will be left stranded if we keep defaulting to fragmented, bespoke transport thinking. At Normod Carbon, we’re modelling multi-hub configurations and piloting rail-to-port terminals in dense corridors to avoid that—because the LNG industry took thirty years and billions in stranded assets to learn this lesson. We have maybe ten. If you’re an emitter or port operator weighing options and skeptical about shared hubs, drop me a line.

Data notes

The data for this analysis was downloaded from Climate TRACE where I’ve included emissions data from all sectors across Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Meanwhile, I’ve used the E-PRTR IRDb and PRTR Global Map to cross-reference emissions logs, and the IEPR and E-PRTR as references for regional laws and reporting procedures.

Each sector has unique challenges when it comes to implementing capture capture. Since the aim of this study is to facilitate industrial decarbonisation within the near to medium term, I’ve excluded sectors in my data analysis that either not feasible or especially challenging to decarbonise with current technologies.

Included sectors are: fossil fuel operations (oil and gas refining), manufacturing (aluminium, cement, chemicals, iron and steel, lime, other manufacturing, other chemicals, other metals, petrochemical steam cracking, pulp and paper, wood and wood products), power (electricity generation, heat plants, other energy use), and waste (incineration and open burning of waste).

Excluded sectors are: agriculture (enteric fermentation cattle pasture, enteric fermentation cattle operation, enteric fermentation other, manure management cattle operation, manure left on pasture cattle, manure management other, manure applied to soils, crop residues, cropland fires, rice cultivation, synthetic fertiliser application, other agricultural soil emissions), mineral extraction (bauxite mining, copper mining, iron mining, rock quarrying, sand quarrying, other mining quarrying), buildings (non residential onsite fuel usage, residential onsite fuel usage, other onsite fuel usage), fluorinated gases (fluorinated gases), manufacturing (food, beverage, tobacco, glass, textiles, leather, apparel), forestry and land use (forest land clearing, forest land degradation, forest land fires, shrubgrass fires, water reservoirs, wetland fires), fossil fuel operations (coal mining, oil and gas transport, oil and gas production, other solid fuels, other fossil fuel operations), transportation (domestic aviation, domestic shipping, international aviation, international shipping, non broadcasting vessels, road transportation, railways, other transport), waste (biological treatment of solid waste and biogenic, domestic wastewater, treatment and discharge, industrial wastewater treatment and discharge, solid waste disposal).

I’ve also excluded any point sources that lack emissions data or are located offshore to ensure that mean distances to port and railway are computed accurately when analysing inland transport connectivity. Other than that, I removed heat and power plants from the Climate TRACE dataset because they bundle the emissions from these point sources under a municipal emissions figure, making it impossible to compute mean distances to port and railway. After that, I manually sorted through public records of heat and power plant emissions data, adding the point sources to my consolidated dataset.

With that, I aggregated each point source’s monthly CO₂ emissions volume into a yearly figure before segmenting each plant by total annual emissions volume into small-sized (<100 ktpa), mid-sized (100–750 ktpa), large-sized (>750-1000 ktpa), and massive-sized (>1000 ktpa) plants. Finally, I downloaded global port location data from the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and railway routes from Natural Earth which have been used to compute the mean distances to ports and railway lines while generating the graphs seen in this study.

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is natural gas, primarily consisting of methane, cooled to about -162°C at atmospheric pressure till it occupies roughly 1/600th the volume of its gaseous form to enable efficient, long-distance transportation by sea and storage in specialised facilities. ↩︎

Post-WWII energy shortages in Europe and U.S. surplus production drove rapid pipeline expansions and early LNG experiments for diversified supply. ↩︎

Regulatory backlogs under the 1938 Natural Gas Act led to overlapping interstate/intrastate builds and frozen low prices, stranding investments (1,265 pipeline applications with only 240 approved in 1959). ↩︎

Shared hubs and interstate pipelines enabled economies of scale by distributing gas from southwestern hubs to multiple cities, cutting per-unit costs 20-40%. ↩︎

Economies of scale represent the potential benefits of having a larger operation. In theory, larger operations are able to increase production, buy higher quantities of goods in bulk, and rely on process efficiencies. When these benefits are captured, it is said that a company is capitalising on economies of scale as it is accomplishing more efficient use of resources due to its size. ↩︎

An orders of magnitude refers to the scale of numbers based on powers of ten, where each order represents a tenfold increase or decrease. For example, if a number is ten times larger than another, it differs by one order of magnitude. ↩︎

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) comprises technologies to separate carbon dioxide (CO₂) from flue gases at large point sources such as power plants and industrial facilities, compress it for transport via pipelines or ships, and inject it into deep subsurface geological formations like saline aquifers or depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs for indefinite isolation from the atmosphere. ↩︎

Kilotonnes per annum (ktpa)is a measurement indicating one thousand metric tonnes produced annually. ↩︎

One third is meant as a general impression of the total emissions in the market because not all European countries have been included to to varying data accuracy and accessibility. Included countries are: Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom. ↩︎

Rough calculation based on the data from this study with 2092 point sources where 1626 have annual emissions between 0 and 500 ktpa. ↩︎

Northern Lights is a joint venture between Equinor, Shell, and TotalEnergies, providing CO₂ transport and storage as a service to emitters. ↩︎

Bibliography

Stopford2008 “Maritime Economics”, Routledge

The definitive comprehensive guide to the global shipping industry, blending five millennia of historical insights with rigorous economic theory to demystify the competitive dynamics of modern sea transport. The 3rd edition explores shipping market cycles dating back to 1741, the intricacies of supply, demand, and freight rates across the four key shipping markets, and the financial underpinnings of ship ownership, including costs, revenue, financing, and risk management. Newly expanded sections of the book delve into the geography of maritime trade, principles of bulk and specialised cargo transport, the economics of shipbuilding and recycling, regulatory frameworks, and the art and pitfalls of forecasting, making it the go to reference for students, industry professionals, and policymakers seeking to navigate the blend of logistical sophistication and entrepreneurial vigour that defines this vital pillar of the world economy.

Rossi2023 “Carbon Capture and Storage Deployment in Europe”, Clean Air Task Force

Across Europe, countries are increasingly recognising the vital role for carbon capture and storage in their industrial decarbonisation strategies. Modelling has shown that to achieve our climate objectives, up to 600 million tonnes of CO₂ will need to be permanently stored across the continent by 2050. As part of this large-scale deployment, countries across Europe will need to understand the mitigation opportunities for deployment in key industrial sectors as well as their national storage landscape.

Rodrigue2024 “The Geography of Transport Systems”, Routledge

The mobility of passengers and freight is fundamental to economic and social activities such as commuting, manufacturing, distributing goods, or supplying energy. Each movement has a purpose, an origin, a potential set of intermediate locations, and a destination. Mobility is supported and driven by transport systems composed of infrastructures, modes, and terminals. They enable individuals, institutions, corporations, regions, and nations to interact and undertake economic, social, cultural, or political activities. Understanding how mobility is linked with the geography of transportation is the primary purpose of this textbook.